An Agnostic Argument for a Sunday Morning Renaissance

Six weeks ago I started going to church.

The following is an agnostic argument for a Sunday morning renaissance.

I’ve never had any particular love for Sunday. Our brothers and sisters of Abraham, and Ibrahim, prefer Friday and Saturday respectively. That’s fine. Sunday morning is simply the context I’m most familiar with and the one I’ve been enjoying in my community.

My argument is not for a specific day, time, or place, but one of structure, rhythm, and ritual. If I argue this correctly, you’ll see that a Sunday Morning Renaissance won’t just fulfill our social and emotional needs - it’s the most practical thing we could do.

We seem to be lost at sea, and a Sunday morning renaissance may be just what we need to right the ship.

“You do not belong to you…Your significance will remain forever obscure to you, but you may assume that you are fulfilling your role if you apply yourself to converting your experiences and abilities to the highest advantage of others.” - Buckminster Fuller

Note: If you find yourself struggling with part II, I highly encourage you to carry on.

I. Young Zealot

When I was in my late-teens, early-twenties, I was essentially a zealot who bent towards scientific atheism. I tried, like many-a-young-man to convince everyone else of the rightness of my position, even though I didn’t have the wisdom and experience of age and time. I had all the conviction in the world, but no credibility.

Some of the details of my former position still appeal to me. I find it perfectly possible that we appeared in the Great Rift Valley, in the Horn of Africa, some 200,000 years ago, and I do see and feel an odd physical and cultural resemblance to the Great Apes (it’s fairly easy to see the best and worst of ourselves in them). Ironically (or perhaps not) the first time I felt The Bigness I wasn’t far from the Valley where it all began - some 3,000km as the crow flies.

In its totality, I’ve come to see my former position as an immature stance. Not because it gets everything wrong, but because it’s incomplete somehow. It isn’t sophisticated or nuanced enough for an aging brain. It doesn’t have the stuff I need now and it doesn’t have the stuff we need as a people. A people who can’t seem to find a way to move forward together.

Last Sunday I went to my local church alone. I wanted the music, the quiet, and the space to think, learn and journal. Above all, I wanted the people - to embed myself within a community and become a productive member of it.

When the music finished the Pastor had us turn to, wouldn’t you know it, the Book of Matthew. The story of Matthew the tax-man and his journey to being saved. There was a small family in front of me who, perhaps feeling like I was a lost lamb of sorts, invited me to pray with them. The mother and daughter held my hand and said a word or two on our behalf (I haven’t yet learned the particulars of this community) and then wished me a good week. I smiled and thanked them.

What a gift.

There are two things I still believe are likely correct about my old, rather unsophisticated position, and three things I was dead wrong about.

The former will probably make me a sub-par Christian. I won’t be invited to share this opinion on stage anytime soon. But the latter may redeem me to at least the status of being welcomed by my community members to join them in relationship on Sunday mornings.

I’m on the path.

II. What I may have been right about

The first is that I believe it’s possible that all Abrahamic religions (maybe all religions) reach the right conclusion with the wrong facts. Each may be a creation myth, created in a time and place to serve the human need for certainty.

Hurling through infinite space on a giant, spinning ball of lava is confusing, to say the least, and so we needed (and still need) to tell ourselves stories about how this all happened and how to manage it.

I don’t believe we have the details right because the details, in my current view, are unknowable. I call it The Bigness, and I’m convinced that it’s something beyond our technical understanding because we are of its own making. I’m certain David Deutsch would disagree.

“We are only a tiny part of an infinite universe. On our own we can do nothing. But, in a silent miracle, the universe puts its energies at the service of human evolution…If we don’t recognize the presence of higher forces, they can’t help us. We need to feel them in the present.” - Stutz

The facts may be a work in progress, but the conclusion is a beautiful one and, I believe, the correct one - that there is something far larger than us afoot and that we are a tiny piece of its drama. We can feel it. We can carry it with us and we can share it. But we don’t get to know the details. Not yet.

The right conclusion = The Bigness that is us, and we are it

The details = Our creation myths

The second is that I still believe, like many recovering atheists do, that organized religion has an extremism problem. The ideal of the good after-life does well to pave the way for this. Highly intelligent, but rather nefarious, imams, priests, and rabbis take advantage of young men who are eager to prove themselves and be a part of something great. It seems to always be young men.

I do find the concept beautiful though. That we know this life is hard. That we know we’re doomed to fail by any reasonable standard. But we accept this. Still we are loved and all will be well in the end, one way or another. The juxtaposition we need to grapple with is that it leaves the door open for extremist interpretation. Maybe that’s human nature and we’re stuck with it.

I’m optimistic that level heads will prevail.

III. What I was definitely wrong about

Submission to something greater than myself. In my youth I thought submission to higher forces was a weakness. I see it now for what it really is - an unbelievable strength.

“Individually it’s a weakness, but collectively it’s a strength. And if we don’t get this joke we’re going to destroy ourselves.” - Stutz

Deciding to go to church on Sunday morning, for me, is reaching out to the rest of the world and saying I need you. I need you because I can’t do this alone. Nobody can - although we seem hell-bent on trying.

Phil Stutz draws the analogy of a latticework. Imagine a latticework where all lines, both parallel and perpendicular, don’t quite meet. To fill the lattice - to make it whole - we need to draw a little black dot at each intersection.

“What is that black dot? It’s need….If you had no need, the matrix wouldn’t form itself…So if you believe there’s a singularity, a one-ness to the Universe, the force, the power, that would create and maintain that is need.” - Stutz

Church creates exactly the right setting for taking that leap of faith - not just toward The Bigness, but to other people in your immediate community. In part, that’s because it’s uncomfortable. Making uncomfortable decisions is, by definition, strong. If it were easy, it would be easy and it wouldn’t lead to person or communal growth.

It’s one way to directly address the second level of the Stutz Pyramid - what he calls The Life Force.

The Life Force is not a destination, it’s a process - and confidence comes only from working the process every day.

When we’ve found balance at the base level, in our physical body, (a connection that may be as much as 80% of short-term change), the next step is to look at our relationship to other people. In the animal kingdom, wounded chimpanzees isolate themselves from the group. Isolation is a disaster for human beings.

Only once we’ve overcome our inability to meaningfully engage with other people can we reach the third level - connection to ourselves on a spiritual level.

“The meaning of life, with all its pain, becomes comprehensible when you realize that you go out into the world to develop a relationship with yourself.” - Stutz

If this is true, and God is in fact us, we go out into the world to become closer to God (or The Bigness).

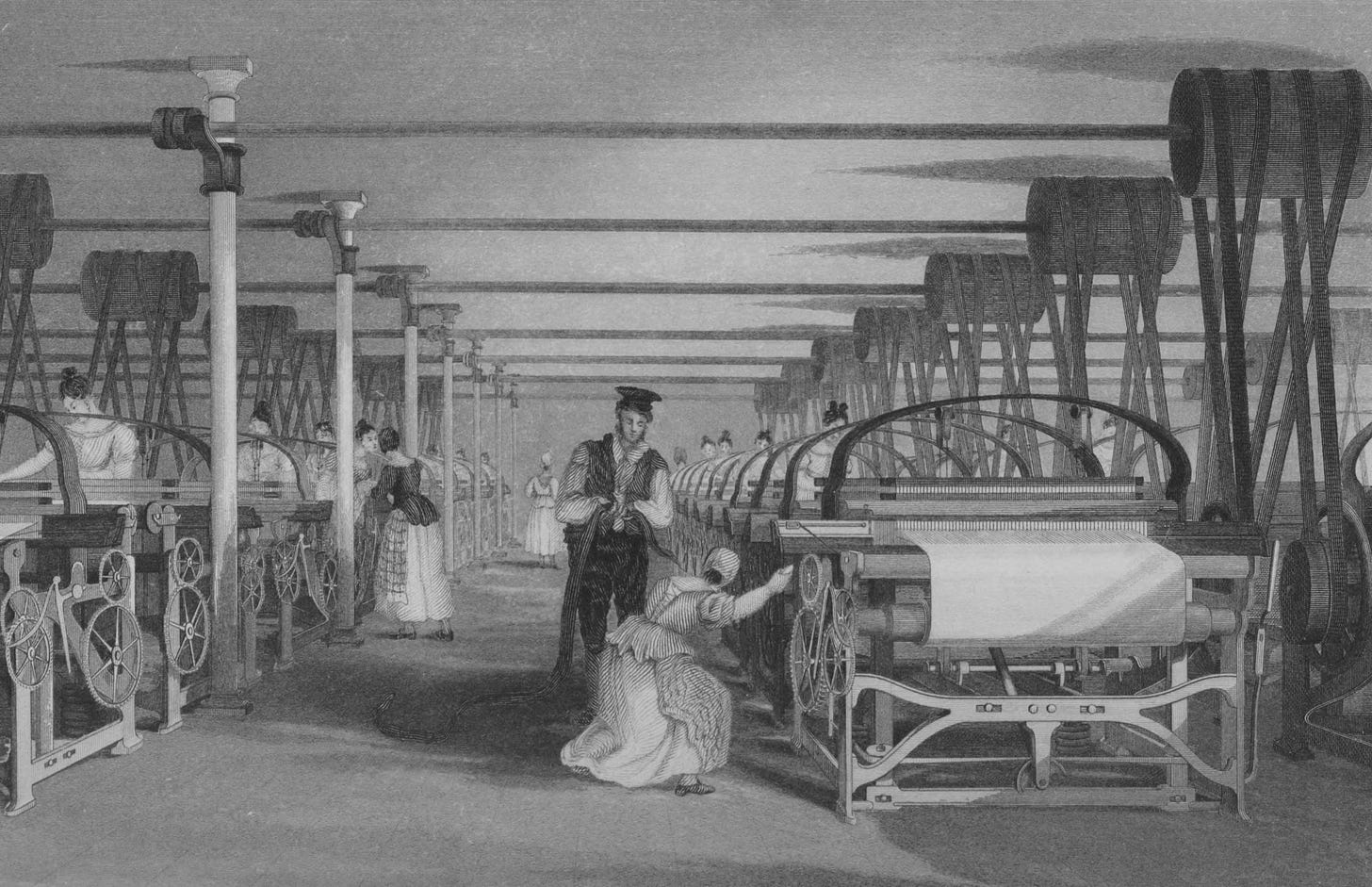

The second mistake I made was having a very unsophisticated view of Christ. Rudolf Steiner said it was the convergence of this and the factory production line that led to a spiritual crisis in Europe around the mid-19th century.

Take advent, for example. Christians would say that advent is about proving to yourself that there is nothing outside of Jesus Christ that will make you whole. The Sunday Morning Renaissance might say something closer to - there is nothing outside of you that will make you whole. Everything external is fleeting and fickle. Happiness comes only from working the process toward becoming more you. And within you, you find what Christians call “the Home of the Lord.”

Or the mythology of The Father. If nothing else, the symbolism is an opportunity to experience death and rebirth. To know that, come what may, you can carry on because you’ve accepted death and you’ve come through the other side.

Barry Michels and Phil Stutz draw the analogy to our mythology of Father Time and to the Jesus story.

“Jesus acknowledges that the will of the Father governs everything that happens to us, and that our role is to accept this. In this acceptance is the potential for rebirth.” - Stutz

The whole of modern life is a refusal to accept how small we really are. And in that refusal, there can be no rebirth.

That’s sophisticated stuff.

I couldn’t see the nature of that symbology in my zealot years. Zealotry closes you off to the next set of ideas coming for you. It’s extremism in a clever disguise of practicality and pragmatism.

The final thing I was wrong about is thinking that society could function (and survive) without third spaces. It can’t and it won’t.

You’ve likely heard the term before. Third spaces are, very simply, somewhere that isn’t work or home. There is great meaning to be found at home and there should-and-could be a meaning revolution at work. As Will Harris says, “Lord bless me with good, hard work to do, and the strength to do it.” But in our current moment of joyless urgency we’re struggling to find the meaning in what was once a vehicle for dignity and purpose. In some cultures, it still is and we have a lot to learn from them.

Without third spaces we’re out of balance.

COVID did us no favours here. Forget third spaces - which, if you’ll recall, were closed by official decree - work and the home suddenly merged into one. (Fascinatingly, in the younger cohort COVID seems like it simply became another layer in an already forming snowball).

The promise of work-from-home (WFH) or work-from-anywhere (WFA) was a fluidity to work and home life. Digital nomadism, of a kind, that promised a rather bizarre independence. We bought it, and didn’t stop to ask the obvious question - at what cost?

“It’s a principle common to virtually all productivity advice that, in an ideal world, the only person making decisions about your time would be you: you’d set your own hours, work wherever you chose…and generally be beholden to nobody.” - Burkeman

Essentially, that you now have the ‘freedom’ to be alone.

We intuitively know, at some level, that this isn’t the way we were supposed to organize.

“…for pre-modern people, the worst of all punishments was to be physically ostracized, abandoned in some remote location where you couldn’t fall in with the rhythms of the tribe.” - Burkeman

I’m convinced that the nature of the languishing we all felt during COVID (unless you were in the thick of the fight as an essential worker) was exactly that.

“…it felt as though the future had been put on hold, leaving many of us stuck…an anxious limbo of social media scrolling and desultory Zoom calls…in which it felt impossible to make meaningful plans, or even clearly picture life beyond the end of next week.” - Burkeman

What we’re missing in all of our new-found independence is depth. Even the term Digital Nomad is a misnomer.

“Traditional nomads aren’t solitary wanderers who just happen to lack laptops; they’re intensely group-focused people who, if anything, have less personal freedom than members of settled tribes, since their survival depends on their working together successfully.” - Burkeman

The Sunday Morning Renaissance represents an acceptance of our reliance on other people. It’s an intentional attempt at restoring community and togetherness. Of organizing in such a way that represents

“…more willingness to fall in with the rhythms of community; more traditions like the sabbath of decades past, or the French phenomenon of the ‘grandes vacances’ where almost everything grinds to a halt for several weeks each summer.” - Burkeman

Independence comes at a cost and we may not be able to foot the bill much longer.

Perhaps what we really need now is to experience the joys of staying put. Of letting compounding takes its course. Of working with time as opposed to constantly fighting for another sliver that can be used for ourselves.

Remember, the etymology of the word sacrifice is literally, to make sacred. When we fall into rhythm with a team, with our family, with our community, we make that time scared by choosing to be there, when modernity promises us that we could be anywhere.

Like Robert Weinberg, cancer researcher at MIT, who nows works a stones throw for the dorms he used to live in as an undergraduate some 50 years ago.

Perhaps there is great power, and great wisdom, in staying put.

“The world is not held together by independence. The world is held together by need .”

- Phil Stutz

See you on the path.

MG

I’ve always felt this too — that while religion has certainly been the cause of division and even casualties, it also creates a space where humans often do better with it than without it. As you say, the facts may vary from one faith to another, but the end game remains: find your community, resist extreme individualism, and live your life as if others depend on it too. Thank you for writing such a thoughtful and well-documented piece — it was a very interesting read.

Nicely said as always Matt! I'm back in SJ now, see you at Catapult