Darwin in the Shadow of Guachos

On becoming an apprentice

Life, inevitably, is lived in seasons. I’m becoming more comfortable with that fact by the day. This isn’t just ecological - although I am reminded of it as the winds change and the forest greens become orange and reds in the North-East.

It’s also in our work.

In the beginning, we’re new to everything. New to the work itself - having no technical expertise. New to the ecosystem - we don’t know who is who. New to how the work is interconnected into the economic whole - we don’t know the players and we don’t know the game.

In a word, we’re naive.

“In a new job situation, we are ignorant of the power relationships between people, the psychology of our boss, the rules and procedures that are considered critical for success. We are confused - the knowledge we need…is over our heads.” - Greene (Mastery)

If we’re smart, we simply put our heads down and do the job. Eventually, we can see the dots connecting. We’ve built relationships, shipped products and services and we’ve received feedback from the real world. We adjust, as needed, and we make partnerships. We can pivot in real-time - we couldn’t do that before - we simply didn’t know enough.

“...pressed by circumstances, we feel unusually energized and focused…At these times, other people seem less resistant to our influence; perhaps we are more attentive to them…We might normally experience life in a passive mode, constantly reacting to this or that incident, but for these days or weeks we feel like we can determine events and make things happen.” - Greene (Mastery)

What we’re experiencing is the first glimpse of the mystery of mastery. It isn’t a fine line in the sand, like a national border crossing. It’s more a DMZ of some kind. You’re in the in-between-place. Between where you are and where you’re going. You see the inexperience of youth behind you, but you’re nowhere close to the wisdom of age - of a full career and a full life (of which, I believe, there is no substitute).

This isn’t a conscious change. You don’t bring it into being by will alone. It’s a matter of time and experience. Of compound interest - earned through effort and action.

There are no shortcuts to compounding.

You’ll need mentors to get to the other side of the Rubicon. You’ve come as far as you can on your own. According to Robert Greene, this is ‘The First Transformation.’

Without an apprenticeship we’re unable to move toward the stage of fluidity that allows us to prove ourselves as professionals or masters of craft.

It may feel taboo, in this day and age, to need mentors. To humbly bow to the Masters and recognize the need for an apprenticeship. The word need implies vulnerability and we’ve been decidedly invulnerable as a people over the last 25 years. But, try as we might, we’re social creatures and we haven’t come close to shedding that evolutionary baggage. Having capable elders to emulate was literally life and death on the savannah.

We were built to observe and mimic - we can see it in our brains.

“In the 1990s a group of Italian neuroscientists discovered…that particular motor-command neurons will not only fire when they execute a very specific action…but that these neurons will also fire when monkeys observe another performing the same actions. These were soon dubbed mirror neurons. This neuronal firing meant that these primates would experience a similar sensation in both doing and observing the same deed, allowing them to put themselves in the place of another and perceive its movements as if they were doing them.”- Greene (Mastery)

When we deliberately place ourselves in the presence of mentors, simply observing their behaviour is akin to learning. We can start to think in the future, putting ourselves in situations we’ve seen in the past, and respond accordingly. We take those observations and turn them into actions of our own. We start trying.

To try in the real world - in the face of everyone else - is to open ourselves up to the experience that makes this all possible in the first place. You’re born ready for an apprenticeship - all you need to do is take action.

The Ideal Apprenticeship

When we lived closer to the natural world, an apprenticeship was high-stakes. It was often centred around formal rights of passage - something we’ve lost almost entirely.

Often, like in the case of the First Nations of North-America, it involved mental and physical pain. The pain was a metaphor for the passing of the torch. The elders were literally handing over the fate of an entire people to those coming of age, and so they had to be ready for that hard road. To be strong of will, mind and character.

The world is different now, but we’re not. We live in an economic environment that doesn’t need us all, even though we still desperately need each other. We live comfortable lives (too comfortable) and we’ve separated ourselves from what we are.

Like Tootsie Tamanetz says, ‘nowadays people live too far away from each other.’

It’s my contention that this actually makes the modern apprenticeship more high stakes. We don’t have rights of passage. We don’t have ritual. We don’t live close to our families or friends. We don’t have multi-generational households. We don’t know how to shoulder the burden because we haven’t been taught how to do so.

It is up to us to be bold and find mentors - to enter into the ideal apprenticeship.

“The apprenticeship, by its very nature, must be conducted by each individual in his or her own way. To follow precisely the lead of others or advice from a book is self-defeating. This is the phase in life in which we finally declare our independence and establish who we are.” - Greene (Mastery)

But what is the goal of our apprenticeship? What are we after?

“...the goal of an apprenticeship is not money, a good position, a title, or a diploma, but rather the transformation of your mind and character - the first transformation on the way to mastery.” - Greene (Mastery)

This is incredibly helpful because it sets the scaffolding for our decision making.

There is a Freakonomics component to this in my cultural context. Most of us carry the debt of student loans. We get degrees that we rushed into, only to carry a 5 figure (or worse) burden in our early 20s - just entering the real world. This pushes us way up the risk curve. Our tolerance for risk goes to 0. And so naturally, in our self interest, we take jobs we don’t care for because the salary allows us to service our looming debt. What a foolish system. It compromises what we’ve learned about the ideal apprenticeship.

“...you must choose places of work and positions that offer the greatest possibilities for learning. Practical knowledge is the ultimate commodity, and is what will pay you dividends for decades to come - far more than the paltry increase in pay you might receive at some seemingly lucrative position that offers fewer learning opportunities. This means that you move toward challenges that will toughen and improve you, where you will get the most objective feedback on your performance and progress. You do not choose apprenticeships that seem easy and comfortable.” - Greene (Mastery)

More on this later. For now, a story of Charles Darwin’s apprenticeship.

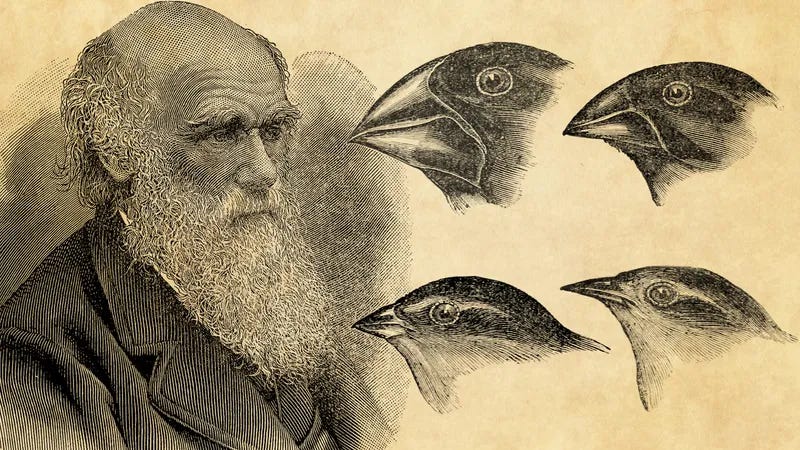

Darwin in the Shadow of Guachos

Charles Darwin’s father didn’t think his wayward son had many prospects in life. He tried to steer him toward formal education, first to Edinburg to study medicine, then to Cambridge to secure a future position in the Church of England. Both ultimately failed. His mind would wander. He wasn’t suited to formal education or a life of contemplation. Charles wanted to be out there.

“He loved the outdoors - hunting, scouring the countryside for rare breeds of beetles, collecting flower and mineral specimens.” - Greene (Mastery)

At Cambridge he caught the eye of Professor Henslow, because of his natural aptitude for botany. Henslow recommended Darwin for an unpaid position aboard the HMS Beagle. They were setting sail on a multi-year journey to patrol the earth’s coastlines, collecting and cataloging the natural world they encountered and sending samples back to England to be studied.

His father said no, and convinced Charles that it was the wrong decision. It was unpaid and unknown. It didn’t offer a straight path to a solid career. What would he do with this? What were his prospects when he returned?

Charles, in pursuit of the possible, wrote to Captain FitzRoy and accepted the position.

“My second life will then commence, and it shall be as a birthday for the rest of my life.” - Darwin

It was hard. The seas were strong, high and wild. Darwin didn’t have his sea-legs. He sat with his struggle and decided that he would lean in, treating the ship and their far-off ports as his laboratory.

“This now was his world. He would observe life on board this ship, the characteristics of the various sailors and the captain himself, as if he were taking note of the markings of butterflies.” - Greene (Mastery)

He would throw himself headlong into an apprenticeship that would ultimately transform his life.

Months later the Beagle arrived on the shores of Brazil. It was teeming with life. South America was validation of the choice that Darwin had made to persevere. The interior of South America had never been studied by a foreign naturalist. The various peoples indigenous to the land were the only true experts and so, naturally, it was in them that Darwin found his mentors.

“Determined to see every form of life that he could possibly find, he began a series of treks into the Pampas of Argentina, accompanied only by guachos…” - Greene (Mastery)

He apprenticed himself entirely to the ways of these regional masters. He would closely observe how they moved across the land, adopting their ways and tried to fit in to local culture as much as possible.

If not for having been in tow of the masters, he wouldn’t have seen half of what he could see otherwise. If he hadn’t learned to see the land the way they saw it, he may not have developed the taste for adventure that came to him in Argentina.

It wasn’t just how the masters moved through the physical world. It was how they saw the land and its inhabitants in time. That everything, according to their world view, was in a constant state of change. That the natural world ebbs and flows with time in a way that wasn’t aligned with the static world view of Darwin’s England. This was a turning point - a realization that would inspire the genesis of what would become his theory of natural evolution.

“He began to wonder - if such species had died off long ago, the idea of all of life being created at once and for good seemed illogical…”- Greene (Mastery)

Darwin could feel himself and his mind transforming.

“He used to find almost any kind of work boring, but now he could labor all hours of the day…He had cultivated an incredible eye for the flora and fauna of South America…More important, his whole way of thinking had changed. He would observe something, read and write about it, then develop a theory…ideas were sprouting out of nowhere.” - Greene (Mastery)

His apprenticeship transformed his work. He was able to see connections in his area of study, to develop theories rapidly, and to test them in the field. He returned to England with ‘…a seriousness of purpose and sharpness..the opposite look of the lost young man who had gone to see years before.’

Thankfully for us, Darwin’s apprenticeship - and those of countless other Masters - have been documented and dissected.

It appears, not without coincidence I’m sure, that the ideal apprenticeship phase takes place in 3 steps.

That’s next time, here on the newsletter and the podcast.

“Genius too does nothing but learn first how to lay bricks then how to build…”

- Friedrich Nietzsche

See you on the path.

-MG