How Not to Get Stuck in The Past

Things have to work

Last time we continued down the path of what is becoming a rather fun series, based on Chris Arnade’s How to Build the Perfect City.

Point 1: Everyone - everywhere - wants and needs community

Point 2: City planning has a clear role to play and is in many ways top down

We talked about regulation vs. trust and how the ideal scenario for any people and place seems to be a little of the former, and a lot of the latter.

What we do do in the former category needs to be thoughtful, well communicated, and has to work. This is often not the case but it’s a fair aspiration both at the group and individual level.

“The classic example being the well-worn dirt path cutting between useless sidewalks, or the now mostly unused vast concrete plazas built by city planners from the 1950s to the 1970s. Albany’s Empire State Plaza, being the closest example to me.” - Chris Arnade

What we do in the latter needs to be from the bottom up - from us and not ‘them.’

That’s why the Europeans tend not to have the same naughty view of nepotism as we do in the West - at least at the margin. It’s an expression of how much they value trust, and how much of their societies were built to function around that simple human need.

Why wouldn’t you open a restaurant with your spouse? Westerners would tell you not to mix business and family, while the Europeans and Asians wouldn’t bat an eye at the prospect - albeit likely for different reasons.

In a hyper-diverse world, where economic development is essentially entirely based on the idea of bringing more people into the place (small-town Canada) the idea of attempting to establish trust is seen as exclusive. Asking about one’s family connections for example, is read as ‘If you don’t have any, we don’t want you’ when really all it is is trying to find a first point of contact and familiarity.

When trust is low (again - the modern West) we don’t give each other the benefit of the doubt, and so everything feels high risk in social life. Don’t try to establish trust, don’t excitedly ask questions about family heritage, don’t do much of anything at all beyond the normal pleasantries because you will likely be labeled as something that you are more than likely not. This, obviously, makes community life very thin.

It’s probably easy to see where I’m heading here - and you won’t be surprised to know - that I think is a recipe for disaster. In this scenario, we live in the same place, but we share nothing, and we trust no one.

It’s what makes urbanism and birthrates perhaps the defining story of our time. Diversity done well is a wonderful thing. It adds a dynamism to the local economy and social fabric that you couldn’t get any other way. Done with a laissez-faire attitude and without sincere consideration, it likely leads to a high regulation, low trust society where we don’t agree on much of anything at all, and where we can’t establish a culture that helps us all understand who we are, where we’re going, and what our role is.

How we move forward together - and how we craft policy that supports the collective - allowing most people to navigate the times well is what we’re going to talk about today.

Point 3 in How to Build the Perfect City is that all policy is downstream of culture. In principle, that may be hard to stomach, but in practice - if you’d just look up and out at the world, and not down at your screen - is perfectly obvious.

Please enjoy!

“Given the age of the shop, it’s in pristine condition. The counter polished, the trains without any dust. The egg sandwich actually an omelette sandwich with a bit of jam. (Yum.) The coffee strong. The music classical. I’m the only one here. Sitting in the corner looking at this incredible scene — truly a life’s work, a work of life.” - Craig Mod

Policy is Downstream of Culture (Aussie Aussie Aussie!)

Chris learned variations of what we’re talking about here both by walking and riding a Greyhound bus through the Australian North-East, heading West into the fringes of the outback. It was a really excellent series that reminded me of my time in Australia as a young man, and what I learned there.

I remember doing mostly young man things - biking, walking, running, hiking, swimming, climbing, rugbying, and mingling with the fairer (smarter) sex. But I do have flashes of deeper experiences like how much I learned from my international counterparts - especially the Scandinavians who were almost absurdly stereotypically excellent, and who I think about often. Especially Asbjorn and Andres, because of how much they taught me about discipline, common sense, and a strange practical joie-de-vivre I didn’t expect from the tall, fit, handsome, serious men. Serious, but quick to laugh, is a combination I find endearing.

Andres recently returned to Australia (having - I kid you not - found a Canadian named Andrea), taking up a post in Sydney’s crown technological jewel - Canva, after a long stint at home, in Sweden, at Spotify (where all young tech minds seem to go in Sweden).

Sweden - and perhaps much of mainland Europe - seems to be going through a startup renaissance at the moment, and I’m keenly interested in how and why.

I also remember the same feeling of self-consciousness of Townsville that my hometown has - a world away. One of those places nobody tells you to go, actively recommends you don’t go there, but also - as a matter of fact - have never been themselves. Once you arrive, you’re more charmed than you expected to be and naturally become curious about the average value of a regular person’s advice.

Chris’s experience was somehow much shorter, yet thicker, than my own. Likely because I was so young, matured late, and was much more interested in finding adventure and risk in a place that seemed to offer plenty of both.

I said in the last post that you really get to know a place by experiencing it on an average day. That’s what makes the coffeehouse or the cafe the ideal way to get to know a people and place - the stage for an average Wednesday, where most people simply go about their boring (yet beautiful) lives.

“Long-time readers of this newsletter already know my views on this, which is that culture trumps policy.” - Chris Arnade

There are no reels with impressive music, no YouTube vlogs, and no movie trailers to be had here. What there is though is new young mothers getting back into the flow of daily life, babe in tow. Business people meeting to discuss potential opportunities to collaborate. Old ladies meeting for tea dressed wonderfully - as all older ladies seem to be. Hourly wage workers behind the bar who care about your experience, and a gathering place that is also a living, breathing thing.

There is no calcification in a coffeehouse - it isn’t a museum, or a tourist trap, or something that has pressed pause on time. It’s working. It’s working right now and it will continue to work, day in and day out, forever, as long as we keep showing up and patronizing. There is simply nothing like having a local, and these are sacred places to me.

That is - it won’t surprise you - exactly how to not get stuck in the past. Simply make sure the place works. It can be for tourists too. It can even celebrate the past - perhaps an even greater history than it enjoys now. But it has to work. For the baker, the butcher, the fish merchant, the produce people, and for the customer.

Craig Mod - a modern mensch - writes beautifully about these spaces in Japan - a country that understands craft and local entrepreneurship in a way that I envy deeply.

That man is this man - the proprietor of a small, unique, whimsical cafe in Toyama, on the mid-west coast of Japan, tucked gently in to Toyama Bay, as if the Sea Japan was putting it to bed and reading it a storybook.

Distribution and frequency of local shops is as important to the dynamism of a place and it’s economy as anything else I can think of - employing 90%+ of all employed people, and allowing the rest of us to create a life of ritual, routine, and relationship.

“The citizen’s default behaviour (in the aggregate), is a reflection of their culture at the thin and thick level, and acts like a guidebook everyone carries in their back pocket, gifted to them at birth.” - Chris Arnade

Taking photo walks around my hometown, the place I work on and live in, has been a great rebirth of joy for me in recent years. As you age, you realize that the most trite wisdom is the most true, and so advice like ‘think global, act local’ is actually very good advice.

There’s a policy analogy here too, in that generic policy that is adopted and implemented without considering the reality of the people and place in particular, may not work for those living there.

If you’re going to grow via immigration, for example, then your People Gains have to be matched with Productivity Gains, and if they aren’t, you’re going to get things like a shortage of housing and unsustainable wait-times in emergency rooms. You’ve invited families that need all of the services humans need, without an underlying acceleration of productivity that would ensure those services are available and stay available.

Done well, both in tandem could lead to a great future - one that includes one of Chris’s keys for a livable place - ‘…density, and localized distribution.’

In plain language - are the things that people need in daily life - cafes, shops, pharmacies, churches, and doctors office, readily available and accessible? Can you move through the community easily, cheaply, and effectively, like in Seoul and unlike the hell-sprawl of suburban commuter-towns in the West, like Orlando.

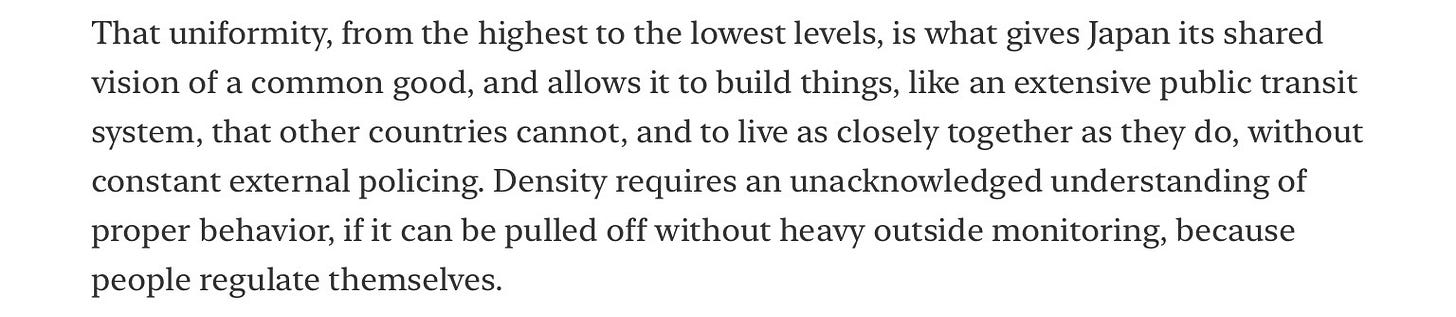

Trust plays an underrated role in how we build a place, and how we behave as people. Things like mixed-use-zoning - a lovely idea that is successful in some European and Asian towns, and is, according to Chris Arnade, barely possible in a place like modern America.

“Americans are fearful of shared spaces because they don't trust each other, and compared to Japan they are correct not to. Americans don't self-regulate to the degree Japanese do, and to quote a line from Bob Dylan, far too often in American life, you find out that "the pump don't work 'cause the vandals took the handles."

But remains very possible, and very stable in places like Japan.

Like an individual getting stuck in a rut, entire cultures can be path-dependent that way. We get on trains that feel somehow hard to get off of, and so we make idols out of things we ought not to idolize.

If you’ve read this newsletter for some time you know that freedom and independence are both in that category for me - and our obsession with both has landed in us in a cultural and spiritual death-roll.

“…we end us as a nation where everyone thinks of themselves as a master of their own small fiefdom, which means building high walls, with homes on one side, and businesses on the other.” - Chris Arnade

We demand privacy, quiet, predictability, and comfort and the odd result that we somehow didn’t expect is loneliness, selfishness, and dopamine addiction.

“There is a fine line, which is all about public trust, between vibrant, alive streets, and squalid, fetid, lurid ones, and Japan is on the right side, and we (the US) is on the wrong side of that line.” - Chris Arnade

I told you last time we’d deal with the US vs Europe thing, and deal with it we shall! That’s next time, the final post in this series, about how the policy decisions we make do change culture (even if they won’t fix us).

—

All we need is a point of view, a set of tools, and a lot of time.

See you on the road.

“How does a culture change? Mostly through persuasion.” - Chris Arnade