IN PRINT: Fly Tie Dreams

For 'The Maritime Edit' Magazine

I was published in print for the first time in 2016. That’s when I found my voice, as it were. Or maybe better - when I found my style. It was the story of historic spring floods in my hometown, juxtaposed with the changing cultural tide, flowing rapidly at the same moment as the floods. Both worlds collided in an unexpected way that excited me.

I pitched the story and it went well. The editor of the magazine liked it and they’ve given us a very long leash ever since. Creatively, that’s a real blessing.

In the latest issue (on shelves now) Mark Hemmings and I tell the story of Fly Tie Dreams - the story of mentorship on a famous river.

If you like what you read, please consider supporting the magazine.

There’s nothing quite like print.

I. The Nowhere Place

“I hadn’t know that, when you live on a river, you are never not thinking about it. You see it on waking, hear it in nighttime barges that sluice through it, feel it in the dampness of the air. It’s never the same, rising, rushing, sinking, slow when foggy, thick in the summer, and is also always the same. It is so easily a metaphor that I find myself insisting that I will not allow it to be one. It’s a river.” - Bill Buford (Dirt)

2:30am is the nowhere place. It’s certainly not the night - but you’d be hard pressed to convince me that it was morning either. It's the exact place between here and there. Between nowhere and somewhere. Even the most ambitious locals have long ago answered ‘last call’, and the all too eager anglers are at least two hours away from donning waders and choosing flys.

In every way I can think of, 2:30 am is the nowhere place. And yet, in a small town of 800 people, dead-center-bullseye New Brunswick, in a quiet inn on a famous river, to the bed just left of my own, Chris Weir was wide awake, dreaming about fish.

This is a story about a river, and about fish. It is, like almost everything I write, a Maritime story. Of our closeness to water and to the natural world. Of our closeness as a people. Of New Brunswick’s great mentors and of their young apprentices. Of the passing of knowledge from capable, experienced elders, to naive youth. Of the passage of time, and the evolution of people and place.

II. Learning to Fish

Like Roderick Haig-Brown, I learned to fish in August. From there our stories diverge. It wasn’t in England (although it may as well have been I suppose), it was across the Atlantic, on the East coast of Canada. My maritime education wasn’t postponed because of WWI, it happened early in my life. It was in deep water, not in the rivers. Salt, not fresh. I learned as a rite of passage of sorts. My father is from Newfoundland and my mother, New Brunswick. One of many blended families that make up much of the gene pool of the Maritime region.

I should have known that fishing would eventually come for me. That I would, inevitably, hear the call of the sea.

I was born in 1992 - the same year the cod moratorium hit my father’s home of Newfoundland. A deep scar on the culture. As intimately personal as it was economic, in a region characterized by a thriving commercial fishery. Generations of fishermen were forced to haul their boats on to the shore. In the short-term, it was an effort to let the Ocean heal itself after years of a commercial fishery taken too far. In the long-term, it was a siren song for the end of an era and way of life. The future was coming for Atlantic Canada like a milk-white fog bank.

To this day, I can’t listen to Darcy Broderick’s Will They Lie There Evermore without feeling a lump in my throat.

My paternal history is one of water. My grandfather was from Random Island, Newfoundland, and on Random Island fishing was a way of life. My family didn’t earn a living from the fishery but every year, when the winds changed and the air turned from cold to cool, they’d fish - more often than not, until the freezer was full. My education fishing deep water started with a simple hand line and a large hook, often with homemade loures crafted from the handle of a kitchen knife. Simple, but effective

Thick, creamy, white cod filets. Two inches thick. Cod-aux-Gratin (pronounced, Cawd-o-Grahtin, with the French accent most assuredly missing). Fish and Brewis (pronounced Fish-n-Brews) and scrunchions. As was the time and character of the day, we would fish with my father and grandfather, clean and filet the catch, then immediately hand over our wares to my aunt and grandmother, masters in the kitchen with local ingredients.

My first mentors were my grandfather, his long-time outdoor companion Fred Best (the mayor of our small town) and my father. As young boys we would watch their behaviour closely, trying to emulate them as best we could. It was our first apprenticeship in the natural world - the same feeling that I experience now in freshwater, on New Brunswick’s famous rivers.

III. Chris Weir

When we lived closer to the natural world, finding good mentors was a high-stakes game. It was often built in to formal rights of passage involving mental and physical pain. The pain was a metaphor for the passing of the torch. Of struggle. Of becoming capable. The elders were literally handing over the fate of an entire people to those coming of age, and so they had to be ready for that hard road. To be strong of will, mind and character. To have that thing in the belly.

The world and the economy are different now, but we’re not. Through neuro-biology we see that we are hardwired-ready for apprenticeship. We were built to observe and mimic. Those structures are still intact in modern humans.

“In the 1990s a group of Italian neuroscientists discovered…that particular motor-command neurons will not only fire when they execute a very specific action…but that these neurons will also fire when monkeys observe another performing the same actions. These were soon dubbed mirror neurons. This neuronal firing meant that these primates would experience a similar sensation in both doing and observing the same deed, allowing them to put themselves in the place of another and perceive its movements as if they were doing them.” - Robert Green (Mastery)

When we place ourselves in the presence of mentors, simply observing their behaviour is akin to learning. We can start to think in the future, putting ourselves in situations we’ve seen in the past, and respond accordingly. We take those observations and turn them into actions of our own. We start trying. All the more important in the natural world. We unlock a new level of observation and practical understanding.

Without knowing it, Chris Weir and I had entered into a relationship like this. The former, the experienced mentor, and the latter, a naive apprentice. We didn’t say it out loud. We didn’t shake hands on it. We simply allowed our relationship to blossom through our mutual love of New Brunswick’s water. Through early mornings and first light over the Miramichi river. Through a hot cup of coffee, boiled on the bank, and a shore lunch. Through cold water pools. Through the calligraphy that a float line draws on the surface of running water. Through the rise of fish to a fly.

Chris Weir, unsurprisingly, started his fly fishing journey in the shadow of mentors of his own. Experienced watermen who worked and loved New Brunswick’s rivers. First and foremost, his late father-in-law and grandfather.

Born of the old Maritime cloth - the tough-but-fair type - Chris’s father in law was a school teacher with the hands of someone who was anything but. He always had at least one finger wrapped in a bandage, the result of who-knows-what from who-knows-when. Battle scars of the hobbyist who couldn’t quite seem to sit still for very long. Wood working, fixing up old cars, turning a screw here and a bolt there. In the first days of September, as the new school year approached he could be found in the bathroom, vigorously scrubbing a summer's worth of irritability and grease off of his skin. These were not, I assure you, school teacher hands.

Unbeknownst to Chris we share a long lineage of mentors that were also teachers. My namesake and grandfather, George Martin, who taught me to fish deep water was a school teacher and later principal. George was plagued with the same itch that men of that time, in this place, were plagued with. The inability to sit still for too awful long. A love for active days, the natural world and a cup of tea and a home-cooked meal in the evening.

Chris himself pursued the trade, for a time, before following his deep love of people into the world of professional sales. Chris was never far from the land - tied, like so many, to the natural resources economy of the Maritime provinces. His father is the patriarch of the famous Pennfield blueberry business, McKay’s Wild Blueberries, and Chris spent his summers working the blueberry harvest next to his brother and father.

Fishing, for Chris, is a life-long pursuit. In salt water, from the time school ended to September's return, Chris was with his grandfather, fishing the bay of Fundy, learning how to pick dulse and dig clams. His grandfather was a retired Quartermaster on what is now the Fundy Rose, the ferry that stewards passengers from Saint John to Digby, Nova Scotia. He worked the ferry after leaving an early career in the fisheries, an ultimatum given to him by his wife who came from a farming family. In his retirement, in an effort to reconnect to a natural way of life in Nova Scotia, he took to the ocean again and started his grandson on the water at 5 years old.

Fresh water was no different - Chris has been fishing trout his whole life and started dawning waders and fishing Atlantic salmon runs since the age of 19, when his father-in-law encouraged him to begin the discipline (the school teacher with the hands).

Although his father-in-law loved hunting in the Fall - he grew up on 200 acres of New Brunswick’s moose country - fishing for salmon in July was his true natural love. He brought Chris into that world, giving him the gift that he now passes on to the next generation of anglers.

IV. There and Back Again

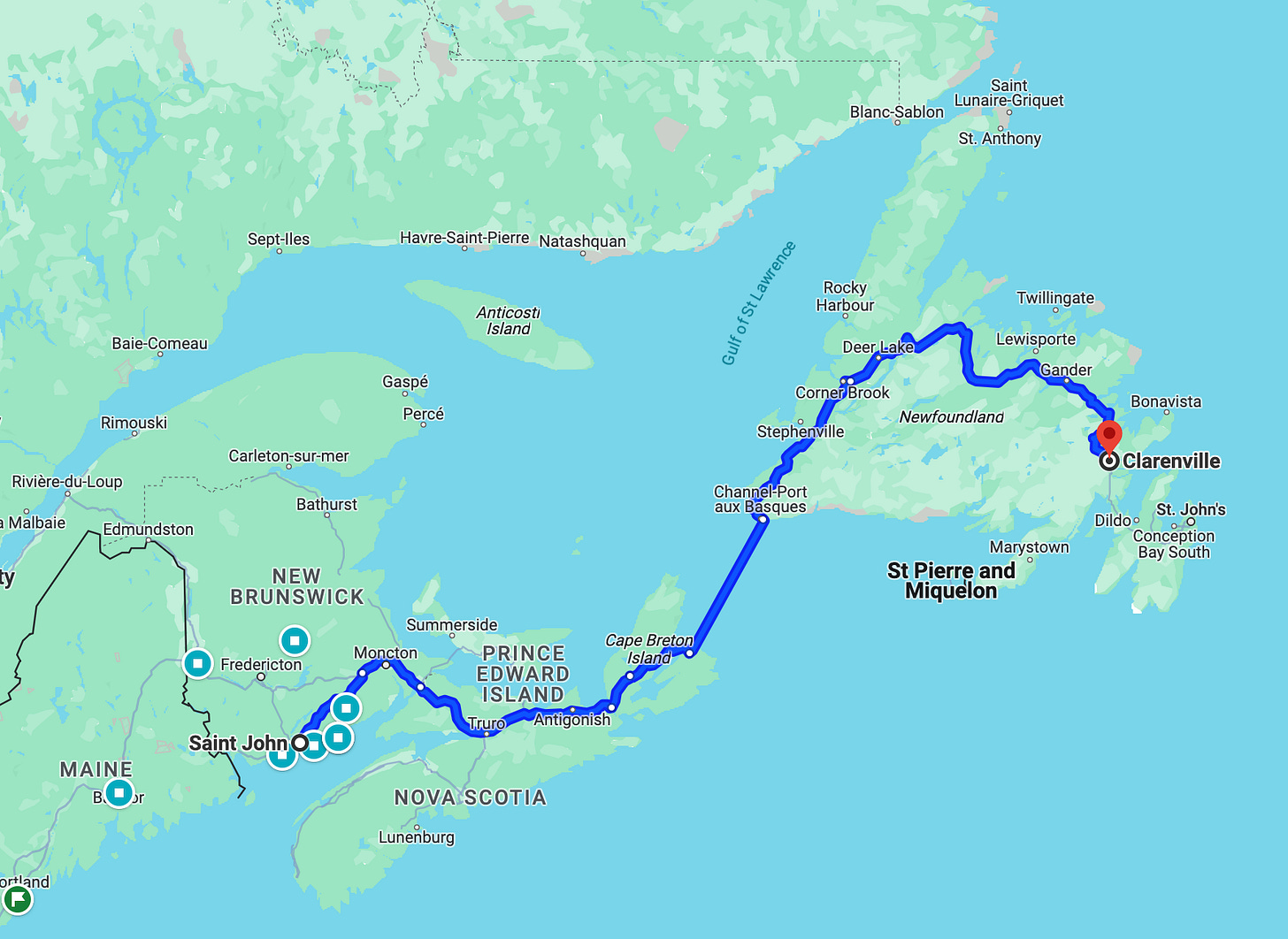

We left Saint John, heading North-East on Route 1, doubling back North-West at the Four Corners of Sussex. We stopped briefly for a hot cup at Picadilly Coffee Roasters. My choice of a warm muffin made Chris reminisce on a life in the blueberry fields. It was almost time for the annual harvest and it was a late year. His father, the patriarch of the Pennfield blueberry business, would soon be hiring an army of seasonal workers to take to the fields.

We left Picadilly for the 10, through Berwick, splitting Kierstead and Snider Mountain down the middle. The 10 turns into the 123 at Chipman, and it’s virtually a straight, forested shot to W.W Doak - one of New Brunswick’s storied outfitters.

Our pursuit was a romantic one - as many things in the outdoors tend to be for those cut from a Maritime cloth - my first fly rod. There is, undeniably, a romance to fly fishing that simply doesn’t exist in spinning reel fishing. It exists to some degree in deep water - but that’s probably because of saltwater fishing’s deep ties to Maritime economies. Fly fishing is different somehow. There is a lore and romance that is equal parts folktale and reality. Watermen trade secrets, fly tying methods, fly patterns, gear, and technique - passing them down like totems from the river itself. If you’re buying your first rod, you can’t do much better than W.W. Doak.

W.W. Doak has been in business since 1946 - the tail end of the second World War and at the very beginning of a renaissance of the North-American outdoorsmen. Folks returning from the war had money, work, and an incredible post-war optimism. They built homes, started business, made families and took to the outdoors in their spare time. It was the heyday of the modern American outfitter.

As it pertains to the fly-rod itself - that’s the ‘Where were you when?’ moment in fly fishing. Every generation has one. For our grandparents it was the assassination of JFK or the moon-landing. For our parents, and us, it was 9/11 and for the most recent generation it will be the COVID-19 pandemic. In fly fishing it’s your first rod and then your first salmon. Both, a new dawn of sorts. When you cross the Rubicon and begin your apprenticeship, in earnest. You’re not borrowing gear anymore, the training wheels are off. You’re going to land your next fish with your own rod, that you picked out, purchased with your own hard earned Canadian dollars. That you waxed, that you staged, that you ran the line up through, that you tied the leader on to. You took a long hard look at the river, breathed it in, looked at the rock seams, the foam lines and the tail outs from fast moving pools and chose the fly that you felt good about (having convinced yourself of this for no good reason). You tied the fly on yourself and you made the first cast, stroking line out as you watch the action of the fly and felt the pull of the river.

That’s the feeling I was after.

I was adamant that this would happen on this trip with my mentor, and at W.W. Doak. I wanted to embed the history of the Miramichi river and all Maritime anglers before me in that rod. The kit that Chris Weir recommended was the one I would buy. So it would be. This is the way of things. He chose an 8-foot salmon rod. A PEI-dirt brown Redington Path - 8 weight to be able to stand up to the fight of a powerful Atlantic Salmon.

I asked Chris about his first rod, later, in front of the fire at Catapult Coffee House, knowing he sees the romance of the river in the same way that I do.

His first rod was a Christmas gift. One of those magical mornings for a kid about to embark on a lifelong mission of connecting with water and with Salmon. It doesn’t surprise me then, that Chris wakes up each morning of a fishing trip, like it really is Christmas morning. Like a child unwrapping his very first rod, knowing that this gift in particular trumps all other knick-nacks and trinkets because of what it will mean a lifetime from now.

Our staging grounds for the day was Ledges Inn. A well-known fishing lodge on the banks of a particularly beautiful stretch of river, downstream of Weaver Island and upstream of the Atlantic Salmon Museum in Doaktown, the very pool we would be fishing the next morning.

V. The Morning Of

It’s the nowhere place again. 2:30am and Chris Weir is lying silently, in the bed next to mine, dreaming of fish. I know, intuitively, that some of those dreams are on behalf of me. He wants the same thing for me as he wants for himself - connection with the river, with fish and with success in our shared pursuit.

At 3:30am, two-hours-and-change before first light, it was time to slowly stir. The morning was warm - too warm. We regrouped, headlamps on, at the tailgate of Chris’s truck and considered our gear, having laid it out as best we could the night before. We drove silently to the parking lot of the Atlantic Salmon Museum and took stock of the morning, sipping on espresso that photographer and friend Mark Hemmings had made in the quiet dawn at Ledges. The colour spectrum of dark blues and blacks, just before the light turns, stirs emotions in anglers that few other times do. Certainly the cool, calm of dusk is romantic in its own way, but it isn’t dawn. It isn’t the start of a new day, full of possibility and encounter.

I had a small, plastic case of my grandfather's old flies - flies that he tied himself - and my father’s tattered old, sea-foam green fishing vest. We donned our waders, slipped on our hats, and staged our rods. I didn’t take it for granted that I was threading my line through the rivets of the rod and tying on my grandfather's fly for the first time - a little brown bug that has become something of a celebrity in this stretch of the Miramichi river. Folklore, passed down from angler to angler - never quite based in fact but never entirely fictitious either.

We walked down the dewy bank to consider the river in earnest for the first time. Chris dipped a temperature gauge. It read the water as the same temperature of the air - above 15 degrees. Too warm. We walk up river, headlamps on, the water gripping against our legs as we walk mid-thigh-deep across a depression in the river for the opposing bank. The sun will rise down the river, to our immediate right, and light up the sky fire-pink.

We fish two famous pools, without feeling the shockingly exciting pull of a strong, young salmon. In fact, without feeling even a hint of it. Such is the pursuit of fishing. You win some and lose many more. We go knowing that, like in life, there are no certainties - and yet still we go, with a stubborn smile, knowing that we will be back, apprentice and mentor, over and over again, until the final bell tolls.

VI. Coming Home, As Always

Some days later, I arrived at Catapult Coffee at the open, set down my Americano and books, crossed my legs and felt the sun creep down Princess Street over my right shoulder. I got a call from Chris Weir. We talked about his family, their connection to the land - from salmon to blueberries, to the bees that pollinate them. We talked of his mother who recently died of dementia and how, in some way, there’s an analogy to be made to the Miramichi River.

He talked about how introducing me to the river, my apprenticeship on a once mighty salmon run, felt like introducing me to someone with dementia. Someone like his mother. Someone, or something, who, however temporarily, forgot how to be. Forgot how it used to be. We fished the perfect pool and both came away feeling a sense of aloneness. Two fish eagles circled overhead - that’s a good sign - but the catch they were after wasn’t there. Only us. Only my fly fishing mentor and his apprentice. Only two men, with deep connections to maritime land, hoping the river will remember who it is.

The future of the river is uncertain. The future of Atlantic Salmon is uncertain. And yet, amongst the uncertainty, we return to the river.

And yet still we go.

“Trout are among those creatures who are one hell of a lot prettier than they need to be. They can get you to wondering about the hidden workings of reality.”

- John Gierach, Trout Bum

See you on the path.

-MG

Excellent writing as always, Matt, and it was really fun to relive the fishing adventure!

I loved everything about this. The writing, of course and the pictures and videos. Beautifully done.