The Ideal Apprenticeship

Deep Observation, Skill Acquisition, and Experimentation

Last week I made the case for three practical tools to set you on a path of forward motion. Momentum that, at a certain point, becomes unstoppable.

Working the path + time = compounding.

And as Charlie Munger (RIP) said, “The first rule of compounding is, never interrupt it unnecessarily.”

When we work the path we go out into the world and act. We get immediate feedback from the real world and those around us.

“The truly successful person has the courage to work this cycle over and over again.” - Stutz

The third phase of the cycle of forward motion is Mentors. Or better yet, an apprenticeship.

Robert Greene makes the case for The Ideal Apprenticeship in his book Mastery. That’s where we land today.

“In the stories of the greatest Masters, past and present, we can inevitably detect a phase in their lives in which all of their future powers were in development, like the chrysalis of a butterfly. This part of their lives - a largely self-directed apprenticeship that lasts some five to ten years - receives little attention because it does not contain stories of great achievement or discovery. Often in their Apprenticeship Phase, these types are not yet much different from anyone else. Under the surface, however, their minds are transforming in ways we cannot see but contain all the seeds of their future success.” - Greene

First, a note on the way of things, and the one non-negotiable in the apprenticeship process - time.

I. The Way of Things

I tend to be someone who believes there is a way of things. That there ought to be a way to do things. An apprenticeship - indeed, my own apprenticeship - is no different. Some of it may be self-directed. Some of it probably should be self-directed - especially when you get to the Skills Acquisition phase - but when you’re in the Deep Observation phase you have no choice but to humbly kneel before the Master.

The reason is simple - you don’t know what you don’t know. You’re naive to how the world really works and so you make room for the scale of experience that your mentor has earned through countless reps in the field.

Early in your career, somewhere between 18 and 25 “...we think that what matters…is gaining attention and making friends. And these misconceptions and naïveté are brutally exposed in the light of the real world.”

Eventually we snap out of this delusion and are pulled toward the Masters. Their knowledge and earned insights are owed deference - we can feel it in how they carry themselves and how others respond to them.

In a culture that has largely lost its admiration of elders and experience - in a culture where the young think they know everything there is to know - apprenticeship and humility could not be more important.

“In our culture we have confused physical adulthood with an authentic spiritual adulthood. The ancient world understood the difference much better than we do. Teenagers were initiated into adulthood by the tribe through sacred rituals that encouraged them to give up their childish need for safety and come into their adult powers. A person was not allowed to sit in a tribal council until the age of sixty, since it was assumed that only those who had reached this advanced age had purged themselves of their immature needs for validation from the outside world. Older adults were respected precisely because they were more removed from the world and thus had the wisdom of real selfhood.” - Stutz

An apprenticeship is about passing through from one phase to the next.

“You must adopt such a spirit and see your apprenticeship as a kind of journey in which you will transform yourself, rather than as a drab indoctrination into the work world.” - Greene

II. Time

Time is the one non-negotiable in the process. We pass through three acts of apprenticeship in sequence - there is a sense of flow. Great work takes the time it takes and it would be irresponsible of us to think otherwise.

Optimism is great - that’s different - but thinking we’re going to be where we want to be next month or next year creates hopelessness. We quit because we expected rewards we didn’t earn and that didn’t come. We have a sense of cosmic injustice. In a dramatic way, we see this in Viktor Frankl’s Man's Search for Meaning.

“In 1944, a rumor spread that the Allies would liberate the camp by Christmas. Christmas Day came and went but the troops were not to arrive for months. Frankl, who was the camp doctor, relates that he saw more deaths between Christmas and New Year’s than at any time in the camp. He attributed this to the dashed hopes of the prisoners.” - Stutz

In our daily lives it’s less dramatic than that, but not by much because what we stand to lose is the future we’ve envisioned for ourselves, if only we could embrace time.

There is something to be said about micro-time and macro-time.

Micro-time might better be described as focus. Trying to multitask (especially if those tasks don’t compound) is the death of the ideal apprenticeship. It’s the death of the process itself.

“First, it is essential that you begin with one skill that you can master, and that serves as a foundation for acquiring others. You must avoid at all costs the idea that you can manage learning several skills at a time. You need to develop your powers of concentration, and understand that trying to multitask will be the death of the process.” - Greene

Unfortunately for us, we’re born into a culture of distraction and dopamine stacking - jumping at every new opportunity, abandoning our work. Hustle culture was always a fraud, and true multitasking is likely impossible. Better, perhaps, to embrace our limitations and make something sacred by sacrificing everything we could do in favour of what we ought to do.

“Fortunately, it is this sense of outer limitation that makes us stronger spiritually. Once we accept the inherently limited nature of the outer world, our inner world opens up and we are forced to look inside ourselves for fulfillment.” - Stutz

In a very real way our work improves and we find new commitment to work the process. We are able to access what Burkeman calls deep time. The sense of fluidity and flow that comes from being in a zone unobstructed and unencumbered by ideas of time.

Macro-time - when we look at our body of work as a whole - the idea of an overnight success fades away into an illusion. Mastery is born of decades of repetition. Thousands of hours. Years of focus and, above all else, experience. The reward for action and attention over long periods of time is a fluidity to life that only masters get to experience. In a very real way, discipline sets us free because discipline compounds.

III. The Ideal Apprenticeship

Step 1: Deep Observation (The Passive Phase)

There is a way of things like apprenticeship because there is a way of life itself.

Our apprenticeship starts with going back to basics - to Deep Observation. Understanding first principles - sometimes literally starting with the laws of physics - and then working backward to the present.

The world hasn’t changed that much. We haven’t changed that much. The social and economic context has but we are still the product of 200,000 years of evolution in our current form, and many millions more when we were something else. Our mirror neurons are still intact exactly as they were when we came down from the trees, when Darwin walked in the shadow of Gauchos, when Zora Neale Hurston discovered Paradise Lost, and when Einstein worked at the patent office in Bern.

Our goal in the first phase of our apprenticeship is simple - we have to see and accept the world as it really is. Not as we wish it was. Not as it will or may be in the future. As it is, right here, right now.

“And so your task upon entering this world is to observe and absorb its reality as deeply as possible.” - Greene

If we skip this step, all future feedback is irrelevant. It’s feedback from a world that is different from the one we inhabit every morning. This is the fundamental reason why, in this stage, we have to ignore all attention, praise or accolades. They will be fleeting things - things we haven’t earned (and thus won’t compound).

Chasing praise and awards means we haven’t accepted our apprenticeship yet and it will be harder to overcome the green delusions and fantasies that we came in with.

“Instead, you will want to acknowledge the reality and submit to it, muting your colors and keeping in the background as much as possible, remaining passive and giving yourself the space to observe.” - Greene

What we’re trying to observe is the rules that govern the game we’re in, and the structures of power embedded within them.

“You are like an anthropologist studying an alien culture, attuned to its nuances and conventions.” - Greene

In our globalized context, that means turning on the engines of our emotional and cultural intelligence - paying attention to the rules that are out in the open, but also the under or unstated rules that are clearly there, but that aren’t being acknowledged.

You’ll feel the latter most painfully when you make a mistake - and that’s how you know they’re actually more important. Our boss might say that this is a culture of innovation, only to bring you back to earth when you outshine the master (incidentally, the first law of power).

Who can navigate freely in your world? Who seems to be a conduit for good outcomes. Folks who have gained such credibility in your space that business seems to be conducted through them. That’s who has real power and influence.

Whether these rule or power structures are bad or good isn’t your business yet. They simply are. The time will come when it’s time for us to act, but now is not that time.

“Later, when you have attained power and mastery, you will be the one to rewrite or destroy these same rules.” - Greene

There is great power in acceptance. It’s empowering in a way that sounds counter intuitive. If peace is happiness in motion, then to embrace the real world is acceptance in motion.

Eventually you will start to see patterns. You will connect the dots in reverse. Like Phil Stutz’s lattice work, we’re collecting data points with every task the mentor gives us. We can now see how action is non-negotiable. We have to make contact with the real world.

“...you are a failure only if you step off the cycle of creation. To someone committed to the cycle, a negative consequence merely represents a correction.” - Stutz

Step 2: Skill Acquisition (The Practice Phase)

The turning point of our apprenticeship comes after many months of deep observation - “The Practice Mode.”

What we’re ultimately after is tacit knowledge - the kind that comes only from repetitions in the real world. Often this phase is long. Without knowing why we’re doing what we’re doing - without a deep connection to our primal inclinations - we risk quitting before we’ve acquired the foundational skills necessary to move forward.

The Middle Ages, and modern day Japan have something to teach us here - both people/place developed their own apprenticeship system. The former, as a solution to the problem of succession.

“...Masters of various crafts could no longer depend on family members to work in the shop.” - Greene

The Masters needed the one non-negotiable - time - to build the necessary skill in their apprentices to carry the craft. If they were going to give their apprentices their stamp of approval, quality assurance was critical.

“And so they developed the apprenticeship system, in which young people from approximately the age of twelve to seventeen would enter work in a shop, signing a contract that would commit them for the term of seven years…They learned through endless repetition and hands on work…” - Greene

At the end of their apprenticeship, the mentee had to prove their skill - producing a master work or passing a test that certified them as a craftsperson that could take work of their own.

The timeline of ‘Seven years’ keeps rearing its seemingly random head (meaning, obviously, that it isn’t random at all). It’s an homage to how critical time is in the mastery formula - there is no escaping it. It appears in the world of start-ups, it appears in the apprenticeship of the Middle Ages, and it appears in the quiet kitchens of Japan.

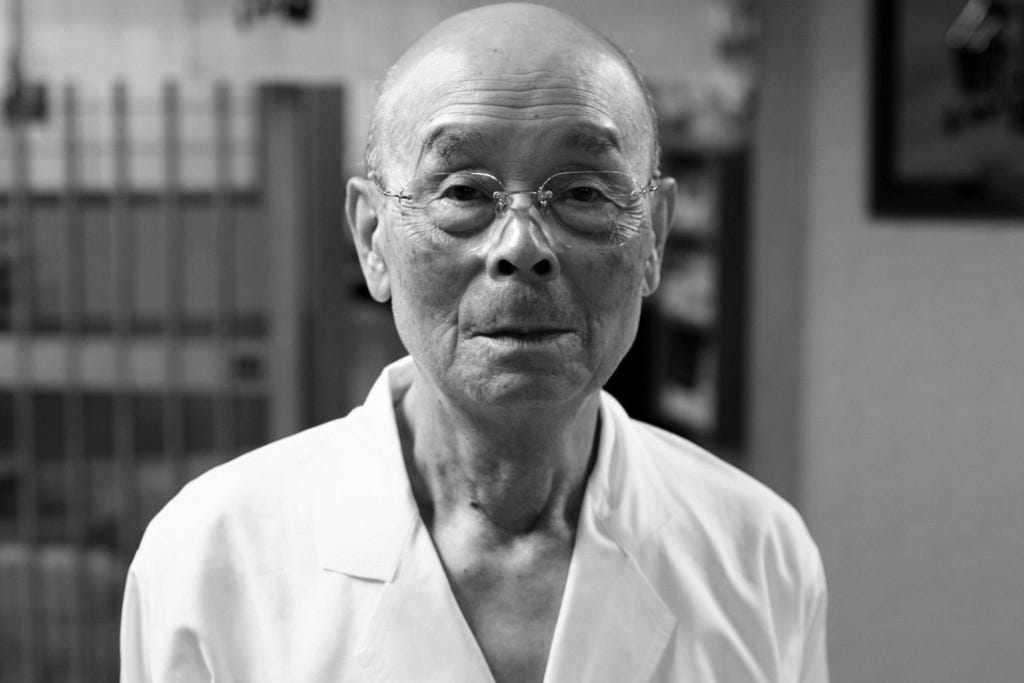

In a 10-seat sushi restaurant, tucked within the Tokyo subway system, found most easily to outsiders using coordinates (35°40'21.58"N 139°45'50.54"E) there is a Master. A craftsperson of the highest order, whom the Japanese reverently refer to as Shokunin.

“The Japanese word Shokunin is defined by both Japanese and Japanese-English dictionaries as ‘craftsman’ or ‘artisan,’ but such a literal description does not fully express the deeper meaning. The Japanese apprentice is taught that Shokunin means not only having technical skills, but also implies an attitude and social consciousness. … The Shokunin has a social obligation to work his/her best for the general welfare of the people. This obligation is both spiritual and material, in that no matter what it is, the Shokunin’s responsibility is to fulfill the requirement.” -Tasio Odate

Jiro Ono is 98 years old, and is one of the greatest living sushi chefs. In Jiro’s kitchen, the apprentice spends seven years just making the rice. There is an obvious (and rather spectacular) reason for this absurd repetition. In fact, it is the first principle of the second phase of our apprenticeship.

“...it is essential that you begin with one skill that you can master, and that serves as a foundation for acquiring all others.” - Greene

The Shokunin cares only about making the highest quality craft. As it applies to sushi, that means first perfecting rice.

This seven years of endless repetition serves a functional purpose too - the second principle of the skill acquisition phase.

“...the initial stages of learning a skill invariably involve tedium. Yet rather than avoiding this inevitable tedium, you must accept and embrace it.” - Greene

The skills acquisition phase, especially in an apprenticeship as high-stakes as those in the middle-ages, or in the sushi kitchens of Tokyo, works to filter out those who are not prepared for the long, hard road. Those who jump from distraction to distraction, going an inch deep in 30 different directions. This life of sampling is fine, and likely exciting! But it is not the path of the apprentice, it is not the path of the Shokunin, and is not the path of the Master.

“The process of hardwiring cannot occur if you are constantly distracted, moving from one task to another…You want to be as immediately present to what you are doing as possible.” - Greene

Step 3: Experimentation (The Active Phase)

Eventually, after miles and miles on the path, we reach the level of skill where we are able to experiment.

“This could mean taking on more responsibility, initiating a project of some sort, doing work that exposes you to the criticism of peers or even the public.” - Greene

With enough feedback - contact from the real world - we begin to feel a sense of flow in our work and we’re able to develop intuition.

“You are observing yourself in action and seeing how you respond to the judgements of others.” - Greene

Intuition is an interesting beast. In some ways, it’s innate. Especially as it pertains to other people. Our intuition is the product of hundreds of thousands of years of evolution. We may trust our instincts less and less today, because they’re become less obvious to us. But if we reach down deep, there they are.

In other ways, intuition is learned - the product of experience. I’ve watched my mentors, sometimes unable even to explain why they think something, call a situation almost perfectly. That’s tacit knowledge. A lifetime of reps in the field. The result of so much experience that, as Ray Dalio says, events start to feel like “Another one of those.”

In the active phase, we begin to put principles around our intuition and can use those principles to form our judgment in any situation. After we’ve proven our judgment correct (or incorrect) over a long period of time, course correction becomes intuitive.

Phase 3 involves taking a leap of faith - trusting that we’ve learned enough through deep observation and skill development, and that we’re ready for what’s ahead.

“Most people wait too long to take this step, generally out of fear…You are testing your character, moving past your fears…You are getting a taste for the next phase in which what you produce will be under constant scrutiny.” - Greene

Next time, a path to action.

“When to quit? The job you’ve worked so hard for? I fell in love with my work, and devoted my life to it .” - Jiro Ono

See you on the path.

-MG

Really enjoyed this read Matt, as always! Good to see Chris + read about Jiro