Lion Trackers & 7 Million Men

I tell stories of people and place.

Almost always more than one, weaving them together like so many strands of DNA. It starts with a question. I go out into the world, like you, and act. Something - inevitably something - comes across my desk and it embeds itself like a tick. An idea or a question I can’t quite shake. Like Michael Lewis and the question of how the Germans (the Germans!) were the last investors out of American sub-prime before the 2008 financial crisis. Like Robert Greene and the mystery of mastery. Like Joan Didion and the curious case of California.

When I have my hair blown back, I make sure to write it down so it doesn’t somehow escape me. When it’s down in my journal I give it time and space. Ideas have to breathe. Eventually, like compound interest, small things turn into big things if given the time to do so.

When enough time has passed and the idea tick has turned into idea lyme disease, I know I have to write about it. It’s the John McPhee thing - all of his many books started as essays for The New Yorker. Sometimes the essay just isn’t enough - the question demands more.

This question is, frankly, unbelievable.

I. 7 Million Men

I recently came across a book called Men Without Work. The book is many things but, at it’s core, it’s about the predicament of the modern man. I can’t help but admit that in recent years I’ve grown concerned about my 21st-century brethren. I can’t tell you why exactly and I’m aware that it’s not popular. It’s more of a feeling. Apparently, not a totally unrequited feeling.

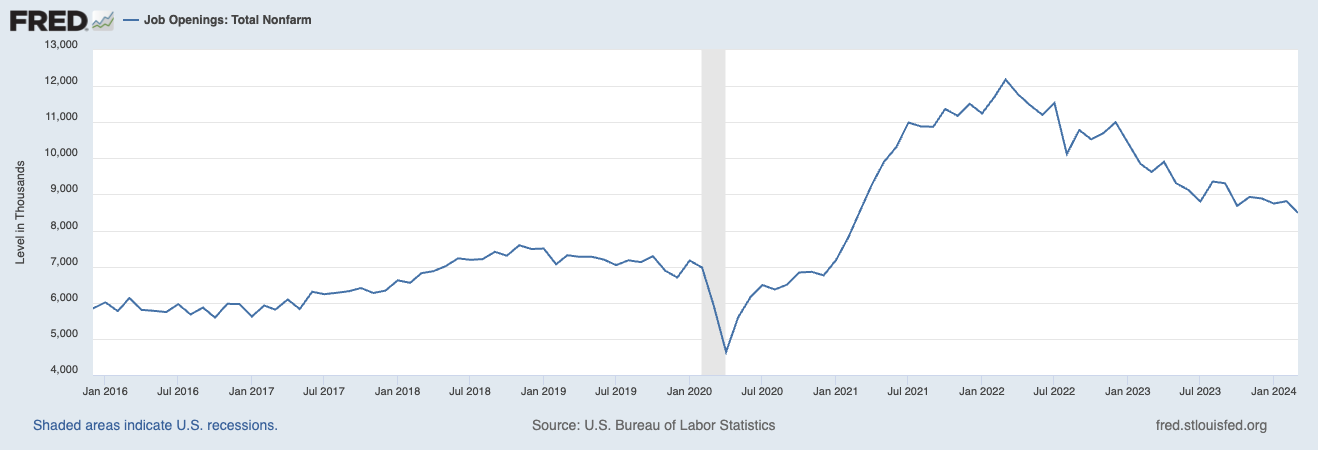

In the book, Nicholas Eberstadt says that there are 7 million American men of prime working age unemployed, and not looking for work. The obvious next question is how that number compares to the number of men unemployed, but actively looking. It’s 4x as high and it’s growing each year.

Alright. Let’s keep going.

The question is…why?

Let’s tackle some basics. When unemployment is low, like it is now, work is readily available. There is more work to be done than folks available to do the work that needs doing. Bridges need building, fences need mending, food needs growing, code needs writing, words need printing, and children need tending to in the many classrooms that can’t find (or pay) quality teachers.

So why are more than 7 million men not in the world doing those things?

For several reasons, apparently.

Like all modern socio-economic issues, it’s complicated. We shouldn’t pretend that it isn’t. We’re eager to paint the world in black and white but that just isn’t the case on the Pale Blue Dot.

Like Mark Twain said…

It ain’t what you don’t know that gets you into trouble. It’s what you know for sure that just ain’t so.

There are people far more qualified than me to address the specifics of what these men have in common. I’m going to forego that conversation, in favour of one I’ve been thinking about since the pandemic.

Is there something about our moment in time that is more conducive to exactly this kind of behaviour? And if there is, how do we find our way back?

II. The Moment

Marilynne Robinson diagnosed the spirit of our time as one of “joyless urgency.” We rush - often frantically - from one to-do to the next. Sprinting through our endless demands of our work only to ship our family freight to and fro, clearing our dinner plates in record time so as to make a mad dash to soccer practice, violin or yet another volunteer committee. And yet, for many of us, we don’t feel like we’re making any progress at all. The gift for our work is, obviously and surprisingly at the same time, more work.

Oliver Burkeman calls it ‘the efficiency trap’ and I’m willing to wage my annual salary that every one of us has felt that eerie sensation more than once. That there is no end. That this goes on forever and I can’t possibly sustain this pace if that is indeed the case. I’m also willing to wager that in the last 3 years we’ve collectively agreed this phenomenon is getting worse (although there are signs that people just aren’t interested in this lifestyle anymore).

Something tells us there must have been a time when things weren’t this way. That there is an alternative reality, however inaccessible, where we could breathe. Where we could sit by the fire and sip our tea knowing -believing- that we did a great day’s work and it’s okay to rest. Governed by the sun, the seasons, and human connection. This is the entire basis of esoteric-health Twitter - ironically, not esoteric in any sense. A remembering of sorts. The human craving for the time Burkeman talks about.

If it’s true that there was a time where work was not urgent and joyless, the question becomes, what’s different now? Are we different now? Why do we move with a spirit of ‘joyless urgency’ while early humans merely moved with purpose - totally unaware that they were supposed to be stressed by their work.

One possible answer is that early humans were in what Oliver Burkeman calls deep time. They weren’t governed by email, to-do lists, and calendar alerts. They arranged their lives and priorities by the infinite movements of the earth and the place they called home. By the tide, by the sun, by the moon, by the current, by the wind, by the soil. They had absolutely no say whatsoever. The world around them was in charge and they were simply a part of the natural drama. They were doing human work, work that needed doing, and didn’t judge themselves by how much of it they did or how much praise they received after doing it.

“...you were content to play your role in the human drama - a role that countless thousands had played before you, and thousands more would play after your death - without any sense that you were missing out on the exciting new possibilities of your particular moment in history.” - Burkeman

Perhaps that’s our problem. We consider ourselves separate from the very thing we came from. We imagine that we created nature and time, and that somehow both are under our control.

Perhaps the antidote is to remember who we are and where we are. We’re finite humans, on a finite planet, with finite abilities, finite time, and in a human culture that is brand new in the scheme of things.

There’s a problem though. One that I’m not naive to. The problem is, even if this is good advice, that kind of philosophical thought isn’t always accessible to us. We can’t seem to find the time or space in our hustle and bustle to actually do the hard work of receiving that important message.

It has to be more practical or we may never do it.

So how can we take steps -tangible steps- to find our way back?

Well, we could consider what to actually work on and therein, how we spend our limited time. As it happens, I believe the old way and the new are colliding. The modern world of the frantic employee and the old world of the early human that moves through deep time with determined purpose, merely doing the work.

The Boyd Varty Framework

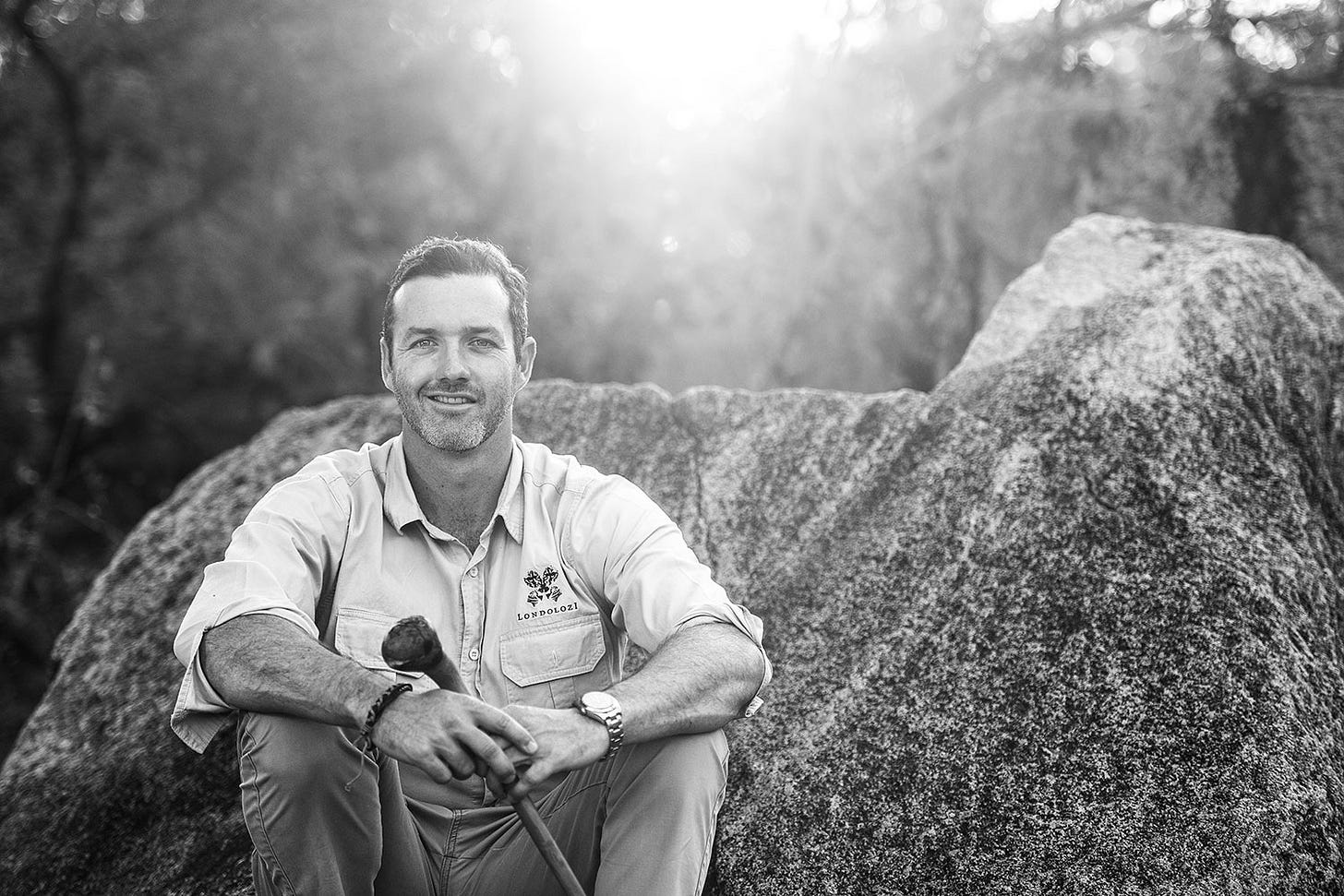

Boyd Varty is a lion tracker who grew up in the South African bushveld, on a game reserve called Londolozi. His grandfather, father and uncle had reclaimed what was essentially dead land - cattle had been raised there and they’d over-grazed the vegetation. With the help of pioneering ecologists like Dr. Ken Tinley, they slowly but surely worked with the land to restore order. Over time, as the soil became a sponge again, the native vegetation and its animals came back to the land. The Londolozi safari business was born.

As a young boy Boyd was apprenticed to some of the best animal trackers in the world. His mentor Elmon would wake him up while the stars were still bright to track leopards, the most elusive and solitary of the big African cats.

What Boyd noticed early was an openness and fluidity with which Elmon, and his later mentor Renias, moved through the bush. An openness to the day and to following tracks, laid down in the dirt - literally on a path from nowhere to somewhere.

Later in life Boyd would use the analogy of tracking to mentor others from the bush to the boardroom.

Here’s the framework he uses - one that I think we can put to use in our own lives when we lose the track.

Waking Up

The first step on our path is to wake up in our own life. The analogy to tracking here is simple. Literally waking up. Waking up early, before anyone else and simply making ourselves available to the day. Physically and mentally making ourselves available to the path. There is no path in stillness. There is no path without movement and openness.

In my experience, the antidote to languishing is curiosity and then action. In my early years I thought ‘follow your passion’ was good advice. Excitement and passion was what I wanted (what I deserved). Now, with age, I see it differently. ‘Follow your passion’ is not good advice - especially for young people. The reason is simple - for a young life, the modern world has far too many opportunities. The possibilities are too big. Real satisfaction - the real path - comes from taking action on something that ignites your curiosity and then building useful skills over a long period of time. From sacrifice and commitment.

Satisfaction comes from getting good at something that is useful to other people.

Satisfaction comes from the path itself.

The Call

Once we’re awake, we tune in and listen. The art of tuning in and listening seems to be something we’ve lost - our human intuition. The things we know we know, but we can’t explain why or how we know. It’s still within us, deep down, but - seemingly all of a sudden - we have to listen more closely. Listen to what ignites that curiosity and what we’re drawn to. It’s there, or thereabouts, where we’re likely to hear the call.

When we hear the call, that of a lion for the tracker, we start to move toward it. We don’t have to know the path in full, we only need to hear the call. The call tells us (reminds us) that there is something out there worth pursuing. And if we’re patient and skillful, we’ll get it.

It might be intimidating, but it’s time to follow.

The First Track

Somewhere along the way we find a first track. Something that pulls us forward toward the call and validates our decision to move. The first track - in this case - is the smallest thing we can do to move toward the ultimate path - which is whatever lies at the other end of that call. We don’t even need a fully formed track! The brush of an elephant's toe, the sweep of a lion's tail as it meanders through the brush, a question that piques our curiosity or an unexpected call from an old friend working on an interesting business.

Move with purpose - this isn’t idle following. The ultimate path is too big. Just follow the first track.

The Path Appears

Eventually those first tracks become a path. You start to see patterns and can navigate among the uncertainty with more confidence. You start to learn the rules of the game. Robert Greene would say it is at this stage that you enter the path to mastery. At some point you’re not learning the fundamentals anymore. You’re moving fluidly, making decisions and adjusting based on your experience of following.

We’re all in now. Full commitment.

Start

So what happens if we lose the path? You will. That will happen. All there is to be done is double back to that first track. You’ve opened yourself up to the path. You’ve heard the call. You know how to follow and you understand the game. You have the experience and skill to move fluidly within it.

Simply start again.

“In his presence the word “mastery” comes to mind. To me a master is anyone who can be themselves in any situation. Renias lives this definition. He has achieved one of the hardest things to achieve in our time: a freedom from judgment about how and who he should be.”

- Boyd Varty

See you on the path.

-MG

Waking up early . . . very necessary but hard for me to pull off. Great post as always Matt!