The Lost of Leadville

Hope for Something

We’re a unique species aren’t we? Ideas embed themselves in our minds like a tick, or a parasite. We can be stuck on something for years. Years! What is that?

Example: Have you noticed you don’t actually need a to-do list? Try it. An experiment. I bet you none of the truly important things in life get missed. The things that matter bubble up and beckon, and the things that don’t matter get left behind, saving you precious time.

Some of the greats have strategies that allow them to use this curious compulsion to their benefit.

Kevin Kelly tries to give all of his good ideas away. If they keep bouncing off of other people and coming back to him - if they just won’t leave well-enough alone - then he knows that’s something he is supposed to do. Nobody else can do it. Nobody else will do it. It’s a uniquely Kevin Kelly thing to do.

Susan Cain has the reality gauntlet. If an idea erupts from the ether she - rather wisely - sits on it for a year. This isn’t idle time. What she’s doing is trying to observe that thing in the real world. If it naturally dissipates and deluminates (no, not actually a word, but as a card-carrying Potterhead I choose Rowling over Websters) then so be it. If it just won’t die, it must be done. The call must be answered.

It’s how I know that I’m supposed to write People & Place. Because I see it in all things. I haven’t read anything like it, and I need it to exist. Craig Mod, Chris Arnade, Gurwinder, and Tomas Pueyo come close, but I know I’ll never be as good as they are and it would be foolish to try. The real move seems to be to follow Steve Rinella’s advice - take bits and pieces of them all, combined into a platform that is uniquely my own.

Yes, like you, I’ve been stuck on many things in my life, but I’m not sure I’ve been stuck on anything quite like the 3100.

In this essay we meet a therapist from the Bronx, the Colorado highlands, a mailman in Finland, the Navajo runners of Arizona, the long wooded road to Japanese enlightenment, and one-god-damn-city-block in Queens that I can’t stop thinking about.

Enjoy the companion track below, and see you on the road.

“If you know the way broadly, you will see it in all things.” - Miyamoto Musashi

TL;DR: We need to hope for something, as individuals and in groups. Communities die when they don’t. We have to work a process, for it’s own sake. Working the process, day after day, is the most hopeful thing we could do.

I. The Snapshot & The Process

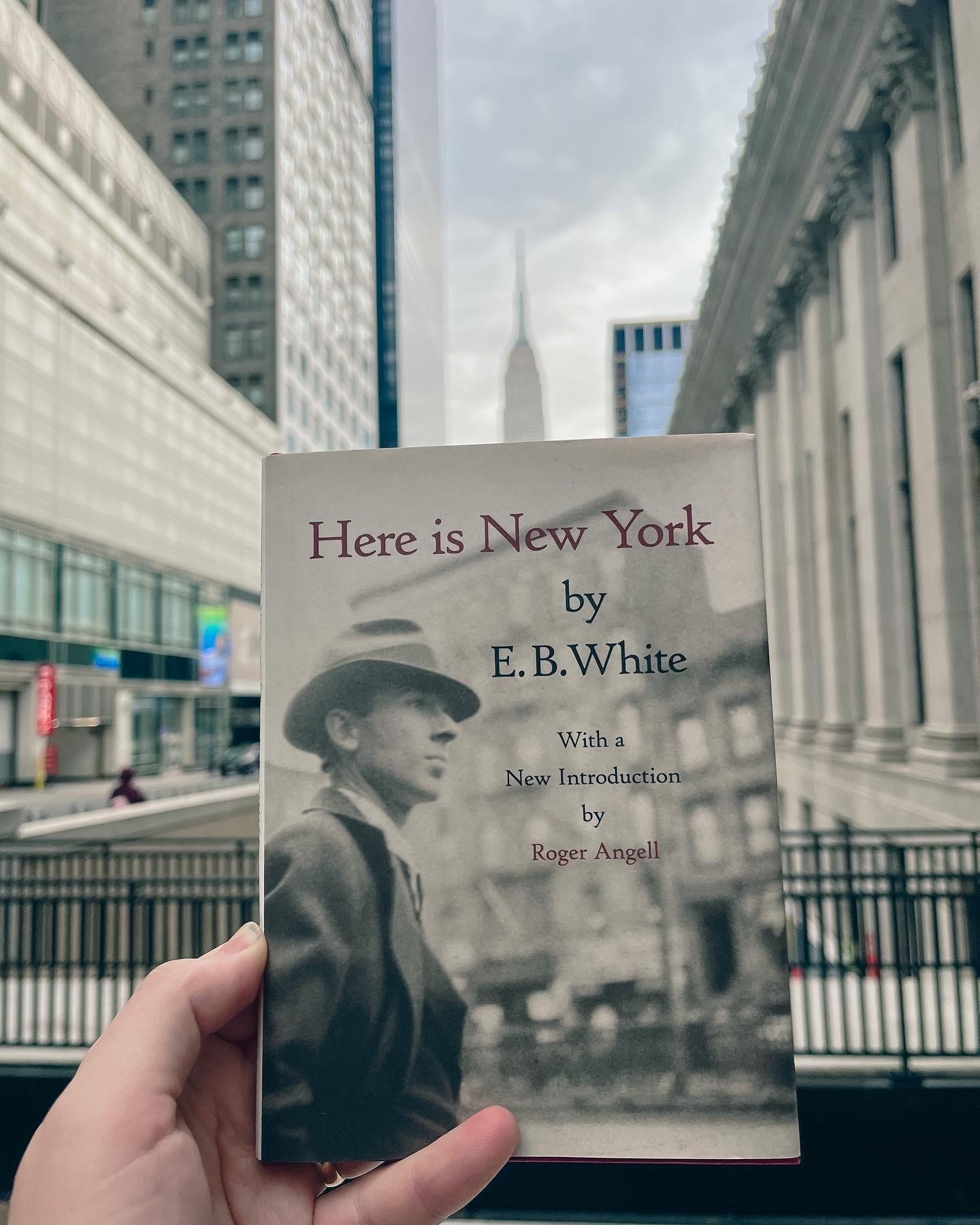

The first time I went to New York City, I thought it unfathomable. You ramble in by train, southbound from Boston, hugging the coast at Pelham Bay Park in the Bronx, across the East River, through Flushing in Queens, then across the river again by way of the Midtown tunnel into Manhattan, marvelling at the sheer scale of it all. You split the Flatiron Building and the Empire State down the middle, before reappearing, squinting in the sunlight, on 34th and 8th street, in the shadow of Madison Square Garden.

What is this?

How in the world does this work? What about the plumbing?! Garbage? Everyone has power? It’s a colossus. An entity all it’s own. Something that nature could never have imagined until the upright, shaved apes conquered every corner and multiplied to billions.

As it turns out, New York City does work and - you could argue - it works really well. Why? Because the culture of New York - the idea of being a New Yorker and New York-ness - seems to supersede all other cultural boundaries. You can be a New Yorker in a way that you could never be Hawaiian, for example.

Living the day in New York, for locals, is a process, and in some immediately obvious sense, you’re all forced into that same process.

It’s the same insatiable noise, the same endless traffic, the same speed, the same rail lines criss-crossing the many sub-economies, and it’s the same enormous urban parks that give locals reprieve in the summer and a sense of escape when they need it.

Ironically, New York itself is the perfect place for this essay because everyone comes to New York in pursuit of their own unique version of the same snapshot. The American Dream, you might say. What starts as a snapshot, quickly turns into the process of being a New Yorker. Of doing all the things that let us agree that we are of the same thing, even though we might not come from that thing.

Phil Stutz grew up in the Bronx in the late 1940s, later moving to Manhattan, and it would be through him that we define the snapshot.

When we forget the process and get suck on an idea, what we get stuck on is the snapshot. The imagined future where everything is perfect. The seas of life turn to glass and we slice right through like Harvard crew. Where we receive the rewards owed to us, in return for all of our good behaviour and good ideas. The irony is that, of course, this moment never arrives. We wait for it forever. There isn’t an end to our work and for some, that’s daunting. What it really is, is a relief. We can forget the rewards at the end - we’re not playing for that.

We show up for the process itself and, indeed, true happiness comes only from working the process.

Entrepreneurs are a good example and they are, generally speaking, a people I know well (Stutz uses the archetype of actors). The best entrepreneurs I’ve met are living testament to the idea that true success comes from working the process - but they all start with a snapshot.

The process is something like this - Entrepreneurs see something in the world that doesn’t work quite right - they spot a problem. They work to understand the experience of that problem from someone else’s point of view and they create a solution - ideally creating it with the customer. Once they’ve proven that they can solve someone’s problem, it’s a creative process of getting feedback and making updates to the solution.

Working the process over and over, in this way, builds confidence. Stutz reminds us that most people believe we can become confident first and then take action. Once I know where I’m going, then I’ll take the action necessary to move toward the destination. That once I have enough money, then I can slow down. That once I have a plan, an apple watch, and a trainer then I can get healthy. All examples of the same conundrum - that once I get that thing in the future, then I’ll be happy.

“…now that has never worked in human history". - Phil Stutz

Deep down we know it’s nonsense but we can’t help ourselves. We don’t want to admit our folly - especially if we’ve been walking that well-worn path for years. We can’t make ourselves believe that the process itself is the only thing that could make us happy and confident, because we don’t live in a culture that is taught to believe that’s possible. We’re taught to mortgage a real day for an imaginary day in the future (the modern definition of retirement).

“But as society accelerates, something shifts. In more and more contexts, patience becomes a form of power. In a world geared for hurry, the capacity to resist the urge to hurry - to allow things to take the time they take - is a way to gain purchase on the world, to do the work that counts, and to derive satisfaction from the doing itself, instead of deferring all your fulfillment to the future.” - Oliver Burkeman

You could call it the Hedonic Treadmill, or Accelerationism, or a combination of the two. When we get what we want, we simply adapt and start wanting other things. Bigger and better things. Shinier things or faster things. Better looking things. New year, new me things.

The snapshot is deceptive because it’s like taillights in the distance that we never catch. The process is the only cure because as individuals, and as communities, we need to hope for something - and there is nothing as hopeful as working the process for it’s own sake.

II. The Lost of Leadville

It’s tempting to use Courtney as the people-poster-child for the process. She’s arguably the best long-distance runner in the world and she doesn’t have a coach, a strategy, or a training program. The average person can relate to the exact opposite. At having barely run a mile but having a written schedule, a goal at the end of it, an Apple watch, new Salomon runners, and a CamelBak just in case we get thirsty on kilometre three. I’m just as guilty as you are.

Let’s instead start with the place - the highlands of Leadville, Colorado.

The Leadville Trail 100 is an ultra-race that takes place in the highest city in North America - two miles up into the backbone of the Colorado Rockies. It was created by a miner in the area, Ken Chlouber - an athletic sadist, cut from a rather calloused cloth.

Allow me to illustrate the point:

“Leadville is a home for miners, muckers, and mean-motherfuckers.” - Ken Chlouber

Importantly, when Chlouber created the Leadville 100 in 1982, he was out of work. In fact, almost everyone in Leadville was.

“…the Climax Molybdenum mine had suddenly shut down, taking with it nearly every paycheck in Leadville…Almost overnight, Leadville stopped being a bustling little burg with an old-timey ice-cream parlor on its old-timey main street and was transformed into the most desperate, jobless city in North America.” - Christopher McDougall

This isn’t a rare story. The industrial revolution brought, among other things, economic hyper-specialization. Entire towns based around the production of specific widgets in a global supply-chain. When that stuff isn’t needed anymore, or someone else can make it on the cheap, things go belly-up. Reminiscent of towns I’ve driven through in the South where all that’s left is old brick buildings with faded paintings of the Pepsi or Ford logo, the corner store, and the local Baptist church.

In the case of Leadville, it was the slow decline of the Cold War. The Moly mine was producing minerals that are an additive to steel. Steel gets uses in battleships and tanks, and when you’re producing less of those things, you need less moly to fortify the steel. The crux of the military industrial complex. The more wars you start, the more money the “defense” supply-chain makes.

“Eight out of every ten workers in Leadville punched the clock at Climax, and the few who didn’t depended on the ones who did…it soon found itself the county seat of one of the poorest counties in the state.” - Christopher McDougall

Important to the Leadville story is work. Although currently out of favour, work is, and has historically been, a vehicle for meaning and purpose.

In the myth of Sisyphus, Albert Camus describes the hero as someone condemned by the gods. His cursed fate is to push a rough stone uphill each day, only to have the stone roll back down to the bottom, when he reaches the peak. Paradoxically, Camus describes Sisyphus as a happy man, because he had his work.

This absurdity - the idea that we can never win - but by doing our duty we find fulfilment is the same ethic that Michael Easter encountered, working for a short time as a Benedictine Monk.

“To my eye, the life of a monk looks a lot like faith-based bootcamp. A monk or nun’s day begins with prayer in the chapel at 3:25 a.m. From there, they’ll run through six other prayer sessions in the chapel, two to four hours of hard manual labor, intense studying, and more.” - Michael Easter

Although it may seem like the Benedictines are condemned to their fate, they consistently rank higher than the average American in overall life satisfaction - the latter being, paradoxically, the very group of humans that has unlimited access to cheap dopamine, sugar, and pleasure, but are getting more unsatisfied by the year.

“In spite of the austerity, in spite of the workload, in spite of all these things that might seem like a hardship and total waste of time, these people are all happy.” - Michael Easter

Perhaps what we gain by going into our communities and working everyday is a very natural, human sense of being needed. A sense that we are moving the community closer to something that is larger than ourselves. When that meaning and purpose is taken away, humans can spiral into a despair that extends to the community as a whole.

“Ken’s neighbors were drinking hard, punching their wives, sinking into depression, or fleeing town. A sort of mass psychosis was overwhelming the city; an early stage of civic death: first, people lose the means to stick it out; then, after the knife fights, arrests, and foreclosure warnings, they lose the desire.” - Christopher McDougall

Hope falls away because all of a sudden there doesn’t seem to be anything to hope for.

Dr. John Perna, who ran Leadville’s only ER at the time told Chris McDougall, in his book Born to Run, “We were slipping into lethal doldrums.”

There was a short-lived glimmer of hope in the tourism industry, but that tends to be overrated long-term (sorry tourism friends).

Ken realized they were in a real pickle, and it was getting worse. Okay then - Ken asked himself - what does Leadville have? Any good accountant will tell you to double-down on your strengths instead of trying to move upstream. Push rocks downhill. Work on what you’re good at. Use your gifts. This is likely an economic development lesson as much as it is a personal one.

What Leadville had was toughness - was an edge that only living at 10,000 feet above sea-level could sharpen.

“If all Leadville had left to sell was grit, then step right up for your hot grits.” - Christopher McDougall

Ken had heard about the first 100-mile footrace in America in the late 70s - the Western States - at the time, perhaps the only official 100-mile running race in the world. This, thought Ken, was exactly what Leadville needed to get it’s mojo back. Something absurd. Something radical. Something that would show the character and spirit of a people and place, like nothing else could. A certified suffer-fest.

Even Chlouber could not have imagined the life his creation would take on.

“…the Leadville Trail 100 boils down to: nearly four full marathons, half of them in the dark, with twin twenty-six-hundred foot climbs smack in the middle. Leadville’s starting line is twice as high as the altitude where planes pressurize their cabins, and from there you only go up.” - Christopher McDougall

To prove the point personally, Ken has run every Leadville race himself - attempts that regularly included hypothermia.

“We’ve got a motto here - you’re tougher than you think you are, and you can do more than you think you can…You don’t have to be fast. But you’d better be fearless.” - Ken Chlouber

The Leadville 100 is a process. There is no prize at the end, other than a silver belt buckle that every runner who finishes gets. The winner still has to pony up the entry fee the next year. It exists because a community - a people and place - needed it to exist, and so it does.

Perhaps the most extreme example of what Ken knew to be true - that we need to hope for something - brings us back to where we started - New York City. To a single god-damn-city-block that I can’t stop thinking about.

III. The 3100 - “Run and Become”

Some time ago I encountered a niche documentary from filmmaker Sanjay Rawal. It’s the dream people and place documentary. The kind of thing that folks like me (like us) get stuck on. In the same conversation as Jiro Dreams of Sushi, My Octopus Teacher, Lo and Behold, and Maradona.

It is, at it’s core, about running. About the running process. About what running means to us, as a species, and what it could mean for us now.

In it, we meet the Navajo runners of Arizona, who run at sunrise to show the Gods that they’re ready to earn the days blessings. We walk the long-wooded road of Japanese enlightenment in bamboo slippers. We meet the San bushmen of the Kalahari, who traditionally endurance hunt, using our unique temperature control mechanisms to exhaust stronger, faster quarry like antelope.

But the centrepiece of the documentary is a single square block, in the bustling borough of Queens - 0.56 miles exactly at it’s perimeter. Chain-link fences, handball courts, ice cream trucks, sweat in the sweltering inner-city summer. Every kind of person, doing every kind of thing, not far, ironically, from where Phil Stutz grew up.

If it’s August, you might see a short, skinny, rather serious looking Scandinavian man with a sun hat, shuffling repeatedly around this single square block. That’s because Queens, of all places, plays host to a monstrosity of the running world. Perhaps the ultimate process. A ludicrous sub-culture within an already fringe culture.

Every summer, the world’s wonderful weirdos of long-distance running gather to attempt to run 3100 miles around this single, meaningless, square block. That’s 60 miles a day, for 52 days, if you’re going for an official finish.

The man you might see, but could easily miss, is Asprihanal Alto, and he’s won the 3100 - the longest certified road-race in the world - nine times.

“I’m simple. Some people believe you need this, and this…all that doesn’t really matter so much. The main thing is to…meditate...and the running itself is the meditation.” - Asprihanal Alto

Asprihanal is from Helsinki, Finland. A unique place for a unique man. Every morning, long before the winter sun rises, Asprihanal rises to deliver Helsinki’s letter mail, returning to his small cabin to make instant noodles on a jet boil. If a 20-something Junior Marketer got ahold of Asprihanal’s motif, it would probably be dubbedvmn y Scandinavian Spartan or Mid-Arctic Minimalist. Nordic Niche. You get the point.

On a small stool by his single-occupancy cot is a framed photograph of his spiritual teacher and mentor, Sri Chinmoy - someone who believed in the unifying power of athletics and created the 3100 in 1997.

“…I found there is no barrier between spirituality and athletics. The inner life and the outer life can easily go together…I feel that physical fitness is of paramount importance in achieving peace.” - Sri Chinmoy

Chinmoy is the man who gave Ashprihanal his running name. He was born Pekka Alto, but was given the name ‘Ashprihanal’ or, ‘Fire inside the heart,’ during his first 700 mile race, because of his unique ability to go inward and overcome. To work the process.

The race location is, obviously, intentional. It’s preposterous. It’s nonsensical. It’s the opposite of epic. It isn’t the red-dirt Moab 240. It isn’t the famous marathon streets of Boston. It isn’t Hope Pass. It isn’t the Western States. It isn’t an Olympic stadium and there isn’t gunfire at the opening. There isn’t fame or glory for the winner and not one of the runners will ever have a major brand deal. It is the literal and figurative antithesis of fame and that is exactly the point.

“The 3100 mile…is the only race…that can guarantee to the runners…you will be changed, and you will be changed for the better.” - Rupantar LaRusso (Race Director)

The pursuit in the Self-Transcendence 3100 Mile Race is intense personal suffering, and absolute commitment to craft. To working the process until it feels impossible to work it for one second longer.

We return to this single square block because the absurdity is the point. We can never win. The snapshot will never be enough. The process never ends. What a relief.

Next time, more on being needed.

“That philosophy argued that, in an absurd world, the acceptance of pain, if accompanied by the commitment to struggle, transforms even the most common men into heroes…recognizing and accepting the futility of his task, he could find nobility in his struggle…In applying our shoulder to the stone, we give order to a chaotic universe.” - Robert F. Kennedy Jr.

See you on the path.

-MG