Policy Won't Fix Us

Regulation vs. Trust

I’ve written a lot of words on Substack. So many words. How many words? Like the fractal dimension of a coastline, it’s almost impossible to tell. I’d have to go back into every published post, hit the edit button, hit the word count button, plug it into a Google Sheet and sum the total. Or I could copy and paste each published post into a giant Doc and let Google tally the word count that way. I suppose it could be done - but what would be the point?

Thin writing - as opposed to thick.

We’ve become obsessed with measuring, numbering, ranking, and labeling things. I’ve been awfully tempted to deploy the list genre that became so popular in magazines in the early aughts, and then popularized online by platforms like BuzzFeed and Cosmopolitan. That is however - not what I’m trying to do here.

Freddie de Boer recently made the point that content on the internet has fragmented into a podcast dichotomy of being expressly counter-culture for the sake of being so, or strangely friendly and commercial - the only point being to sell something, and that something seems to most often be sports gambling products.

I am however deeply interested in the ‘how-to’ genre that was immortalized on YouTube. As it turns out, we humans love to watch each other do stuff (not that stuff you pervert). Build stuff, make stuff, open stuff, sell stuff, play stuff, sail stuff - really all the stuff. It’s the reason that someone like Amazon would back the truck up for a platform like Twitch1.

In some ways this feels natural because we watch each other to learn. The medium may be new - Twitch instead of the workshop or the kiln, but the principle still holds that when the apprentice is in her education, she watches the master for an extended period of time before doing much of anything.

The sushi apprentice watches the Shokunin, and only makes the rice - the base principle of the dish - for up to 7 years. For a seemingly inexplicable reason - the number 7 keeps coming up in these kinds of discussions. So much so that I wonder if it’s actually not random at all - but is somehow the perfect timeframe to learn and make something of value. We can’t truly navigate an industry or craft - you might say we can’t improvise - until we have a freakishly strong base.

And so, I started an essay series last week on Chris Arnade’s How to Build the Perfect City - which is a list of sorts, but is more like a process by which we might make a place that’s worth living in. One that helps the highest number of those living there navigate the times as best they can.

Point 1 was that we all need community and we will do damn near anything to get it. If there isn’t a positive community on offer we will gravitate to negative ones that still offer us something we deeply need - like attention, affection, and acceptance.

“People need community like fish need water, and they need to feel they belong to something greater than themselves. If they don’t have access to healthy communities, they will find unhealthy ones.” - Chris Arnade

Let’s carry on with how to build the perfect city - and see if we can find some more good logic here.

Please enjoy!

“You can't fast forward through the messy parts you might not want to deal with, and you find yourself having discussions with people of all types, many whom you wouldn’t necessarily have sought out to talk to.” - Chris Arnade

Things Become Other Things

The reason we make lists is to compare and contrast things, and use the knowledge we gain to make decisions that are somehow good for us. Things are things, until they become other things, and so we adjust and change and update our thinking (hopefully).

If we can’t do that we’re somehow stuck. We’re not moving forward. We’re not making progress. We’ve lost contact with what I call The Bigness, and what Phil Stutz calls The Life Force. We suffer when we fall out of contact with that thing because - forgive me for the philosophizing - that thing is us.

My accelerationist friends are not going to admire me for saying this - but it seems to me that progress at all costs - progress for the sake of progress - isn’t working, and there is no culture I can think of that puts the individual at the center that has worked long-term. If what we idolize and believe in is something greater than ourselves, we work for the sake of working, because we know that human work is good. If all we believe in is money and the individual, we crumble for lack of spiritual resonance, yet we can’t put into words what we’re actually missing. That’s us right now2.

That thing we’re missing is community. We can only find ourselves through each other, and our modern trinkets like AirPods are seemingly hell-bent on driving us apart, even while we’re physically in the same place.

Somewhere along the line our history gets incorporated into our present - some of us live in the former, more than others. Istanbul, for example, isn’t stuck in it’s history, even though it’s history is oozing from it’s pores. Something I saw first hand when I was 18 years old, but didn’t appreciate at the time.

“It’s a historic city, but it isn’t calcified by it’s past. It isn’t content being a play spot for tourist wanting a taste of an another era. Get away from the must-see tourist spots1 and Istanbul’s long history becomes a backdrop to the good life. A stage setting of sublime architecture, making sitting with friends and family, eating great food, and sipping tea, even more fulfilling.” - Chris Arnade

Some cities are perpetually stuck in their past - and the only thing wrong with that is it becomes hard to move forward and forge a new identity. We can celebrate the past, and what we accomplished there, but we can’t live in it. More on this, and why its so important practically, in the next post

Regulation vs. Trust

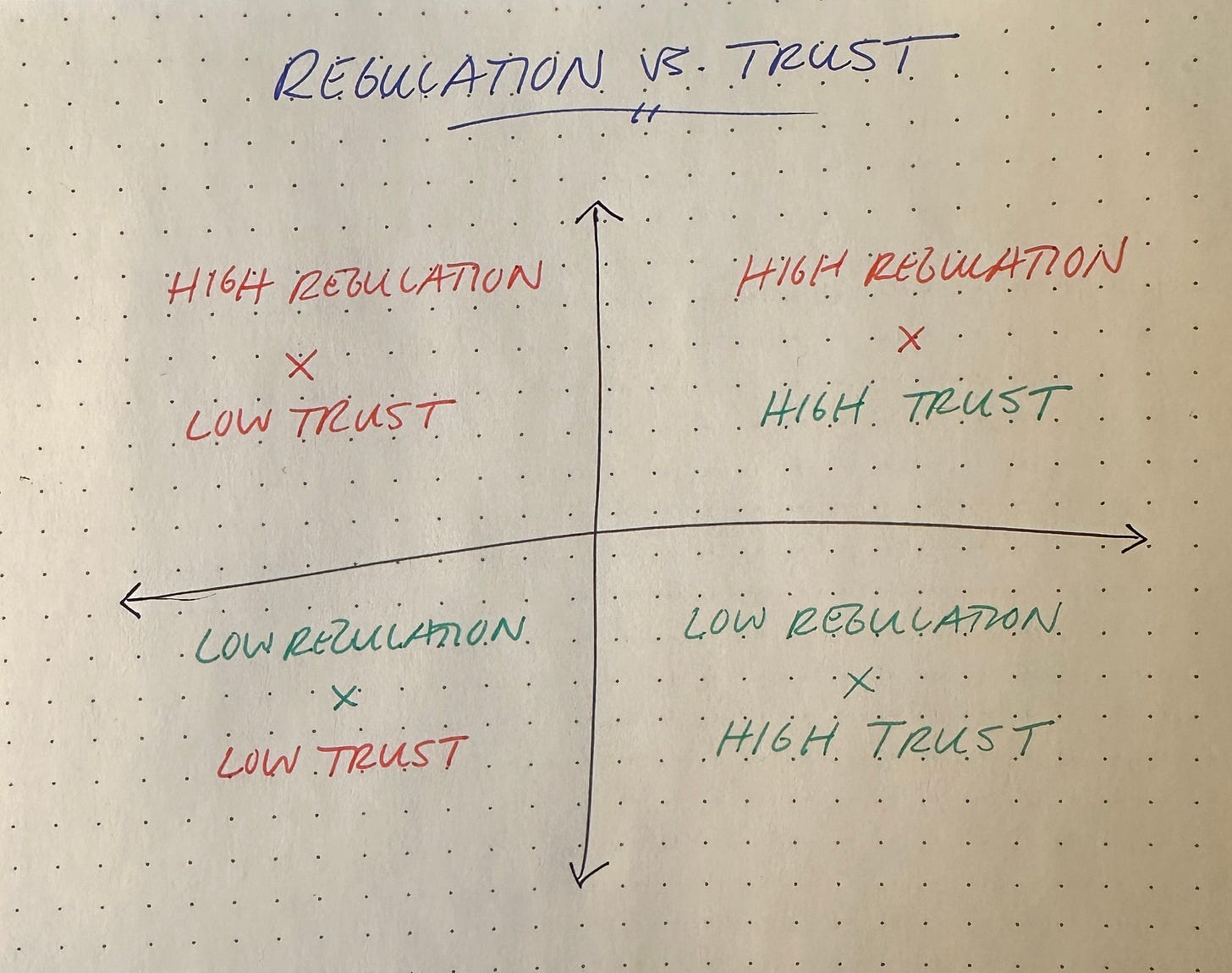

Quadrants are a form of list, and we can use them to contrast the way we position things. I did this constantly as a kid. I’d make obscure lists, ranking things based on different criteria - ordering a world that felt big and exciting.

Two points that are useful to contrast again each other - two I’ve been talking about since later 2016 - is legislation/policy vs. culture. I’ve had many interesting disagreements with close friends in the policy scene that go back to my earliest podcast project, pre-pandemic3.

Chris Arnade was the first Substack writer to crystallize my thinking on this - in a post comparing thick and thin travel. That for a place to actually work, it can’t rely solely on top down planning. This is a fundamental misunderstanding that Westerners have of East-Asian metropoli, like Taipei.

“Peacefully co-existing along side that top-down SimCity mindset is just enough deregulation, just enough of a libertarian spirit, that a bottom-up entrepreneurialism still thrives.” - Chris Arnade

Although Political life in China is centralized, economic life is not. How could it be? China is a nation of $13,000 per capita GDP and yet it’s capable of creating technological breakthrough4. That wouldn’t be possible with a single guiding hand and it wouldn’t be possible without some sense of optimism and entrepreneurialism among young Chinese.

The Regulation x Trust Quadrant looks something like this.

High Regulation x Low Trust seems to be the worst possible place for a society and culture to be. Why? Because you can’t legislate your way out of a broken culture. You may think you can legislate social change - things like diversity quotas - and you probably can to some extent, but it will not solve our most basic human problem of trust. It will breakdown in the end because we don’t actually believe it. What some call The Better Angels of Our Nature.

The agreements we make to each other are what forms the fabric of a culture, not the laws that we all have to abide by, by threat of punishment. If all we can agree on is that we won’t break the law, we are hopelessly screwed as a people and as a place.

To me, it’s because the thing that binds us in that scenario - the law - is not nearly socially, emotionally, or spiritually powerful enough to knit us together, and keep us that way. We cease to believe in anything at all, beyond the policies and the rules that we enforce from the top. The grand idol is the individual, not the collective.

Our problem in the West right now, as far as I can tell, is an us problem and although we can create helpful policies that support our well-being, in an effort to make the default decisions of life healthier, it won’t be the thing that fixes us. That has to come from within the community and inside of ourselves. This is just as true about work as anything else.

This is at the center of a wide-spread debate on Substack that we can generally categorize as ‘The US vs. Europe5.’ More on this later.

Nonetheless, city planning is real, and necessary and Chris’s second point in How to Build the Perfect City is that’s okay to accept.

Public space and gathering is a good example. Do people value access to public land? Is the coastline seen as something like a public good - as it is in Australia? Is there proper infrastructure for active transportation - or transportation that isn’t a car? Do folks gather outside, on patios or in the street, and if they do/will/would, if we zone certain streets for pedestrian use only during the summer months to encourage that kind of gathering?

"If you want to understand a place, you need to walk it." - Chris Arnade

Is there a strong sense of low-regulation entrepreneurialism that allows an economy the dynamism that it needs to truly thrive. We need our beloved local coffeeshops and pubs, as much as we need our large companies that are building breakthrough. In fact, our small and medium sized businesses employ most of us, and so we need strong infrastructure like community banks to support their growth and prosperity.

No amount of policy is going to change who we are at our core, and we shouldn’t expect it to, or rely on it before making changes in our own lives. Policy, it seems to me, should be geared toward maximizing human wellness on an average day. How people behave on a random Tuesday is much closer to the actual pulse of a place than it’s most important holiday.

And so the most important job of those who make the rules is to be closely attuned to the average, instead of pandering to the extremes, like it is so often tempted to do.

“I respect expertise; what I don't respect, though, is out-of-touch, removed, and bubbled expertise…The idea that you need to live what you preach should be a common-sense truth for all expertise, especially urban planning, where, at least metaphorically, you should probably live in the town you design.” - Chris Arnade

Chris’s third point is that all policy is downstream of culture, and we’ll look at that next time - it’s fascinating.

It is us.

—

All we need is a point of view, a set of tools, and a lot of time.

See you on the road.

“The citizens’ default behavior (in the aggregate), is a reflection of their culture at the thin and thick level, and acts like a guidebook everyone carries in their back pocket, gifted to them at birth.” - Chris Arnade

BBC appears to have been surprised by this move - but they shouldn’t have been.

I recently had the great pleasure of trading these ideas back and forth with Pamela Clapp - who I learned about through this post on French culture.

DM me if you’re interested in listening!

According to my AI friends, DeepSeek was a real example of this kind of breakthrough. They figured something out that others hadn’t, and it took most of the West by surprise.

Everyone is getting in the game. Start here.