Cafe Cultura

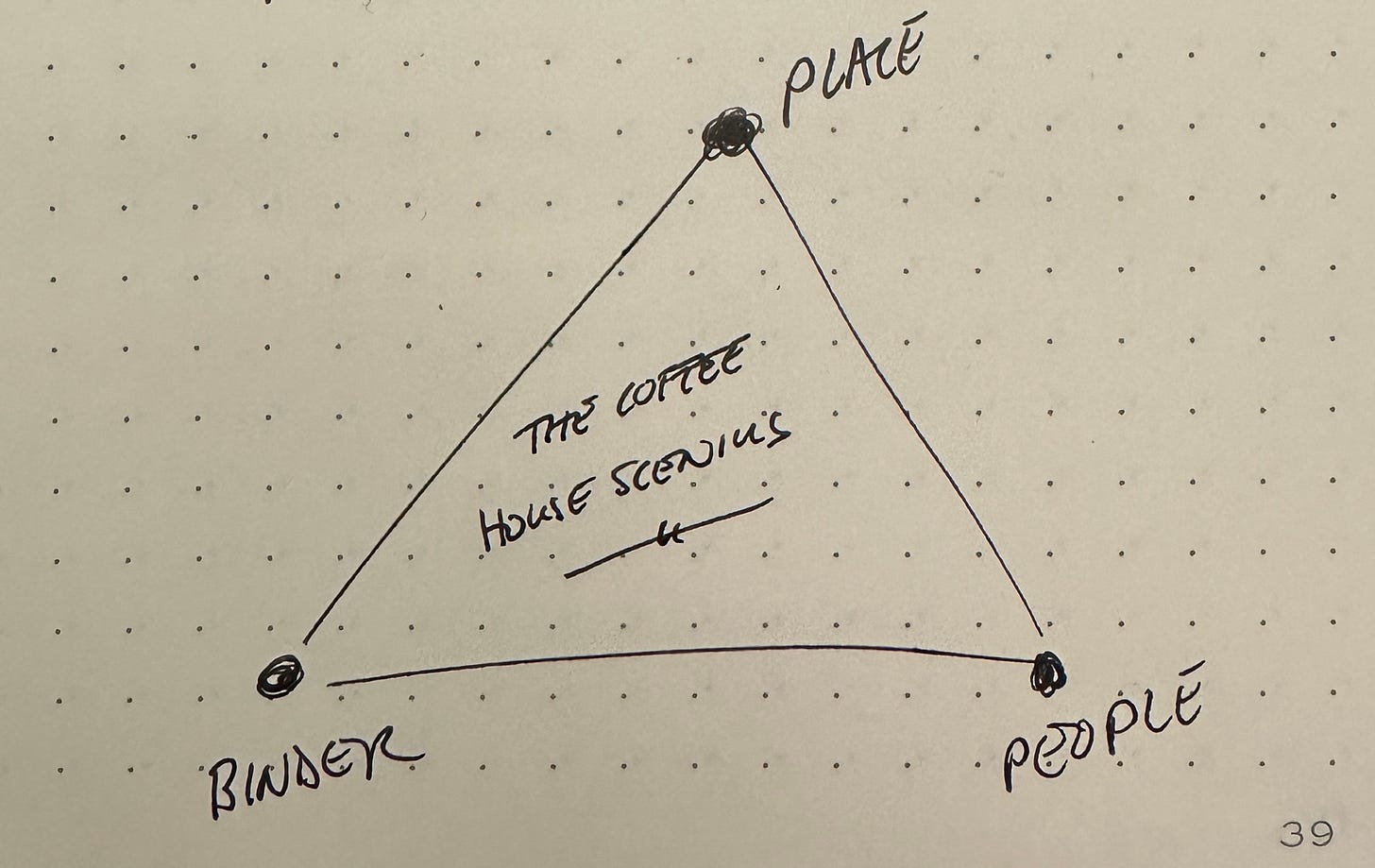

The Coffeehouse Scenius

I heard it through the grapevine that some of you enjoyed having a resonant companion track to the newsletter. You even kept Ornella running on a loop while you processed email and scurried about your daily business. How wonderful.

For this piece, it could have been no-one else. Melody Gardot is inevitable.

From Paris with Love is Naval-ian. What you think you want is euphoria. What you really want is peace.

“Peace is happiness at rest; happiness is peace in motion.” Someone who’s peaceful at rest will end up happy when they do an activity. While a happy person sitting idle will be peaceful. The ultimate goal is not happiness, even though we use that term a lot. The goal is peace. - Naval Ravikant

In some way we know this. It’s not always clear how we know when we know, but that doesn’t change the fact that we do know. It’s something about how the world is. It’s…quiet? You walk into the world, outside of the urban hustle and bustle and the world just…is. No soundtrack. No epic instagram reel. Just life itself. If we can’t find joy there it causes a bubbling up of claustrophobia.

And so, back to the simple pleasures. To the easy joy of the cafe.

Introduction

Last time we explored the first level of the Life Force pyramid.

When we’re lost, we don’t know what to do next. What’s happening is stuckness. We don’t feel like we can access our life force - the very thing that would move us forward.

This is a mistake. Our life force is always available to us, but we forget it’s there and we forget that there is a process by which we can reliably access it. These feelings come in waves. They are natural cycles. Mastery is the recognition that if we have the courage to work this cycle long enough - consistently enough - we begin to transform. Our life force becomes the default state, as it was always meant to be.

It starts with connection to our physical body (we live inside an incredible healing machine that, because of our modern excess, isn’t working properly), evolves into our relationship with other people (chimps are only alone when they walk off into the forest to die), and ends at the tip of the pyramid - our relationship with our own spirit - our raison d’etre. The thing that moves us. We all have one.

Today, we’re moving back up to that second rung - to our relationship with other people. We desperately need each other. We always have.

Interestingly, the last time I wrote about the second rung of the pyramid it produced my most read piece ever. I could tell from the moment I published that this was something you wanted. Nay, something you needed. You likely needed it because we collectively need it.

My argument was simple - we’ve lost our connection to each other and that makes us spiritually poor. It’s a huge mistake. Alone is no good.

And so, this week, an exploration of the coffee house scenius. The world as I see it, from a quiet perch, in our great cafes. The very definition of People & Place. From the rocky shores of the Maritimes, south to the mountains of central Mexico, to the Pacific, to Western Europe and east (always east) to the Levant, and back again.

We all need a local.

“…having all the time in the world isn’t much use if you’re forced to experience it all on your own. To do countless important things with time - to socialize, go on dates, raise children, launch businesses, build political movements, make technological advances - it has to be synchronized with other people’s. In fact, having large amounts of time but no opportunity to use it collaboratively isn’t just useless but actively unpleasant - which is why, for pre-modern people, the worst of all punishments was to be physically ostracized, abandoned in some remote location where you couldn’t fall in with the rhythms of the tribe.” - Oliver Burkeman

Submission Request!

Before we begin - I would love to interact with this community.

Where is your local?

Are you a purveyor of pub life - nestled into one of our wonderful watering holes?

Are you a bookworm - wandering amongst the stacks at a famous library or bookstore?

Are you, as I am, a loyalist of the coffee house?

Is it a bodega, on the corner of a once-or-still bustling city street?

We need great spaces - and great spaces need us. I would be full to the brim if you would share a photo of your local. I’ll share some of the submissions in a later piece on the newsletter.

What I’m aiming at is something like ‘Where do you TGIF?’ from The Free Press. An excellent way to come closer as a community.

TL;DR: We create nothing in a vacuum. Co-creation is only possible with other people because that’s the only way to access higher forces. We need great spaces to gather. I believe the coffee house can, and should be, our next great space.

I. In Search of Scenius

The stone walls of The Eagle and Child - a small, obscure pub on the outskirts of Oxford - contain magic. It isn’t an entirely explainable magic (no true magic is) but I won’t be the first to have tried.

It’s the magic of Scenius.

Scenius is the etymological marriage of the words scene and genius, and it tries to offer an answer to the mystery of - ‘why it happened where it happened.”

The Eagle and Child, often simply called The Bird, played host to a magically productive group of people, in a magically productive place, at a magically productive time.

“Patrons of The Eagle and Child wrote three of the five best-selling fantasy series of all-time within an eighteen-year period – The Lord of Rings, The Hobbit, and The Chronicles of Narnia. It is here, on Tuesday mornings, that C.S. Lewis, J.R.R Tolkien and other members of ‘The Inklings’ of Oxford met to read, discuss, and critique each other’s work.” - Packy McCormick

Tuesday mornings, and Thursday evenings, in the 1930s and 40s, in Oxfordshire were so important to Tolkien that he dedicated the first edition of Lord of the Rings to his time there.

“What I owe to them all is incalculable.”

You can imagine that the times played a role. The when and where of it all. The 1930s and 40s in Europe were eventful times, and art often rises in temperature to match the moment.

“The Inklings of Oxford are part of a long tradition of scenia. The various groups and time periods that represented and played host to scenius are well known - Ancient Greece, The Renaissance, and Bell Labs to name a few.” - Packy McCormick

The burning question behind scenius - how does it happen?

Brian Eno, a giant of the music history, and the one who seems to have coined the term, argued that moments of collective genius started with…. “very fertile scenes involving lots and lots of people – some of them artists, some of them collectors, some of them curators, thinkers, theorists, people who were fashionable and knew what the hip things were – all sorts of people who created a kind of ecology of talent.”

Scenius isn’t structured. You won’t get it by watching yet another video on the 10 Things Millionaires Do Before 7:00am. In fact, our modern productivity beta misses the point entirely.

Warren Lewis, C.S. Lewis’ brother said about the Inklings - “There were no rules, officers, agendas, or formal elections.”

It was pure creation. Often of the wandering and puttering sort. Not in a vacuum - never in a vacuum - but with one another. With a group of like-minded people, rowing in the same direction toward something greater than themselves.

“On our own we can do nothing. But, in a silent miracle, the universe puts its energies at the service of human evolution.” - Phil Stutz

There is no secret, but there seems to be a recipe - one that we will use to try and explain the magic of the coffee house scenius.

We need a place to go, we need something to bind us, and we need our people.

II. Something to Bind Us

Let’s start with something to bind us and move forward from there.

Fiction of the C.S. Lewis sort is true creation. An art. World building. An imagined story, although very much rooted in truth. Alcohol - beer in the case of The Eagle and the Child - can inspire this kind of creative flow. We lose the self-imposed restrictions and confines of sober thought and we can imagine something new.

Non-fiction is more like woodwork. A craft. A discipline. It’s the genre of nicotine and caffeine. Of cigarettes and black coffee - the two main food groups of old-school newsrooms.

The latter was referred to by German naturalist Alexander von Humboldt as “concentrated sunshine,” and it is, unsurprisingly, the binder of the coffee house scenius.

Our human relationship to coffee has been on the official record for a long time.

The Coffea plant has its roots in a relatively small corner of the world - in East Africa and southern Arabia. “…it’s believed to have been discovered in Ethiopia around AD 850..” to a group of goat herders who “…noticed how…goats would behave erratically and remain awake all night after eating the red berries of the Coffea arabica plant.” After reporting their curious findings, the abbot of a local monastery made a home brew of the berries, and there you have it - a revolution (Mendel vibes, no?).

“…by the fifteenth century, coffee was being cultivated in East Africa and traded across the Arabian peninsula.” - Michael Pollan

Once a critical mass of humans were exposed to it’s life giving properties - and promptly began their collective addiction - the coffee plants range expanded as far as Hawaii in the Pacific, the Indonesian island of Java in the far east, “…and now covers more than 27 million acres.”

Coffee’s success, expansion, and subsequent transformation of human culture begs the Kevin Kelly-esque question - who exactly is in control here?

In What Technology Wants Kevin argues that accelerationism is essentially a fait-accompli. We can’t help ourselves. We create new technology and spread it to every urban and rural corner of the globe - even though if pushed to answer the why question it might be something like “Because we can.” We don’t actually know why we’re doing it and that is an equally amusing/terrifying notion.

In the case of the Coffea technology, our hellbentedness on expanding it’s geography to every appropriate growing climate on earth is likely because of it’s “…ability to change consciousness in desirable and useful ways.” It suits, and in many ways drives, our culture of busyness and productivity.

It also happens to be a wonderful thing to gather around.

III. A Place to Go

From the beginning coffee was communal. The at-home coffee ritual was far from nascent, and would have then been unnatural. The brew was exclusively enjoyed together, at the coffeehouse.

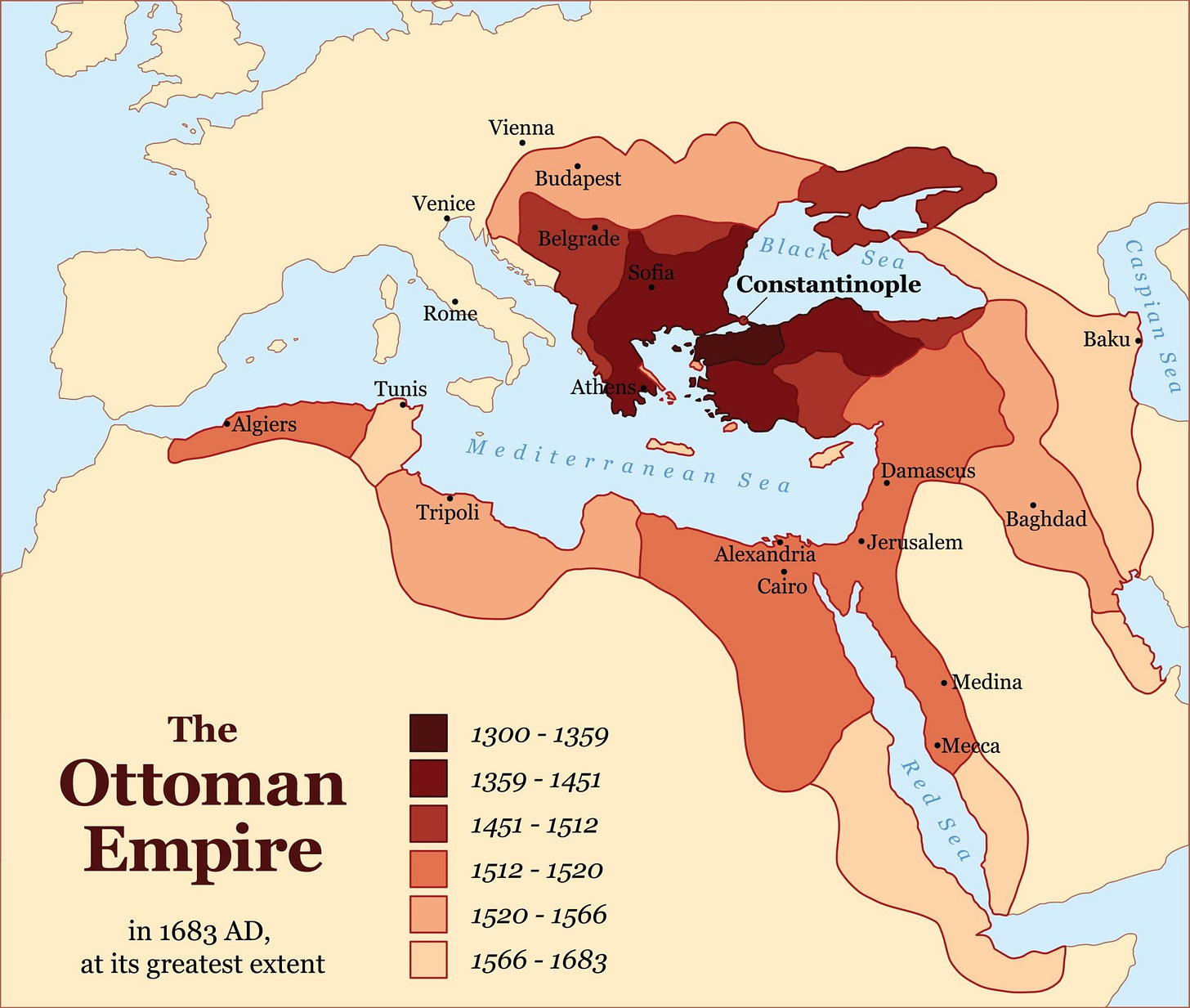

“Within a century [of it’s cultivation], coffeehouses had sprung up in cities across the Arab world.” By the late 1500s, on the south-west tip of the Black Sea, Constantinople was home to hundreds of them.

“These new public spaces were hotbeds of news and gossip, as well as places to gather for performances and games. Coffeehouses were comparatively liberal institutions where the conversation often turned to politics…” - Michael Pollan

The coffeehouse became such a successful gathering place that autocratic governments often tried to shut them down, “…but never…with much success.”

Less than a century later, as the Ottoman Empire hugged the Mediterranean and began its inevitable decline, the coffee house came to Italy. “In 1629 the first coffeehouses in Europe, styled on the Arab model, popped up in Venice,” and the rapid north-west expansion of Coffea arabica was all but certain.

Jacob the Jew, an immigrant to Oxford - the very shire that would later be home to our Inklings - opened the first coffee house in England.

“They arrived in London shortly thereafter, and proliferated virally: within a few decades there were thousands of coffeehouses in London; at their peak, one for every two hundred Londoners.” - Michael Pollan

The coffeehouse became the central gathering place. It was where one got the news of the day and came to discuss important matters of politics, commerce, and life as it was at the time. It’s hard to understate what a place like this could and should mean to a culture.

“To call the English coffeehouse a new kind of public space doesn’t quite do it justice; it represented a new kind of communication medium, one that just happened to be made of brick and mortar rather than electricity and wires.” - Michael Pollan

In fact, coffee was clearly secondary - it was simply a binder that met the time perfectly. It was a medium for the vibrant transfer of information in a rapidly changing, and expanding, economy.

The coffeehouse was and is a true network. It’s a physical manifestation of an idea that we seem to have lost. That no good work is created in isolation. We can do nothing alone, even though almost all modern productivity advice obsesses over our complete control over our time - as if it’s something to be hoarded.

“Yet the truth is that time is…a ‘network good,’ one that derives its value from how many other people have access to it…and how well their portion is coordinated with yours.” - Oliver Burkeman

Networks, it just so happens, are the focus of my work. Economic development is, essentially, the study, and development, of networks. Jeremy Rifkin, someone most millennial economic developers have read (for better or for worse), made a rather good observation in his book The Third Industrial Revolution;

That all economic development is predicated on the energy that powers economic activity, the transportation that moves economic activity around, and the communication that coordinates economic activity.

Coffeehouses in London quickly began to develop natural networks, which had socio-economic implications far beyond the cafe.

“…for example, merchants and men with interests in shipping gathered at Lloyd’s Coffee House. Here you could learn what ships were arriving and departing, and buy an insurance policy on your cargo. Lloyd’s Coffee House eventually became the insurance brokerage Lloyd’s of London.”

In the emerging financial district of London, Jonathan’s Coffee-House was home to the early origins of the London Stock Exchange. The politically inclined got there “…Foreign and Doemstick News…from St. Jame’s Coffee-house.” The Grecian, an incubator for scientists like Newton and Halley, “…which became closely associated with the Royal Society.” Will’s and Button’s, both in Covent Garden, a place to gather for writers and “…the literary set…”

These natural networks allowed for the organic formation of collective identity, something Chris Arnade encountered still-intact in the modern day Rhone Valley.

“The cafe culture, which I saw every day, in every community along the Rhône Valley, is just one example of a very healthy French culture. Of a communal-ism driven not by getting something material from it (work connections!), but rather from being part of a collective, with a shared understanding of who you are, why you are that, and why it’s good to be that. We are French, and this is why we do what we do, and it’s good. It’s a sense of self so ingrained, it’s not explicitly recognized. The water you swim in, but don’t notice.” - Chris Arnade

IV. Our People / Rhythms and Ritual

There are great rhythms and ritual to people and place because they offer us a natural opportunity for this kind of encounter.

“I was there for three hours, and while I was alone, I never felt lonely. I also didn’t order much, and I never felt rushed. The French understand the value of sitting for a long time, around others, while doing seemingly nothing.” - Chris Arnade

We fall in with the ebb and flow of the day, month, or season, and our people and places become the central bodies around which we orbit. We get to experience “…the shared rhythms required for deep relationships to take root.”

A Swedish researcher named Terry Hartig calls this “the social regulation of time.” He discovered that anti-depressant use went down in proportion to how many Swedes were on summer vacation at the same time. His conclusion was one that should be obvious to us, but likely isn’t given our modern confusions around the definition of words like freedom.

Hartig concluded that what we really need is “…more willingness to fall in with the rhythms of community; more traditions like the sabbath of decades past, or the French phenomenon of the ‘grandes vacances’ where almost everything grinds to a halt for several weeks each summer.”

Our people - our communities - lend themselves perfectly to ritual and process. There ought to be a way by which time moves and by which we move within time, not alone - never alone - but with each other.

Great work takes time - it’s true. What happened at The Eagle and the Child took 18 years to play out the way that it was meant to. But scenius can also be felt in small, meaningful moments throughout the day.

Like the fika, in Hartig’s home country of Sweden.

“…the daily moment when everyone in a given workplace gets up from their desks to gather for coffee and cake. The event resembles a well-attended coffee break, except that Swedes are liable to become mildly offended…if you suggest that’s all it is. Because something intangible but important happens at the fika. The usual divisions get set aside; people mingle without regard for age, or class, or status within the office, discussing both work-related and non-work matters…Yet it works only because those involved are willing to surrender some of their individual sovereignty over their time.” - Oliver Burkeman

Or the curious, but delightful ritual of “…the Japanese office workers who rise from their desks to perform group calisthenics at the start of each work day.”

Or in the Bay Area; Michael Pollan’s beautiful daily ritual of people and place with his wife Judith.

“My morning ritual with Judith - after breakfast and exercise at home - involves a half-mile “walk to coffee”, as the real estate brokers now like to say. For some reason we never make coffee at home. Instead, we buy a cup at the Cheese Board, a local bakery and cheese shop, and sip it from a cardboard container swaddled in a warm cardboard sleeve.”

As it turns out, all we need to stitch ourselves back together is a place to go, something to bind us, and our people.

See you at the coffeehouse.

Next time, a short on how things become other things.

“But time — that was the key.” - Craig Mod

See you on the path.

-MG

This coffee related piece was excellent Matt!